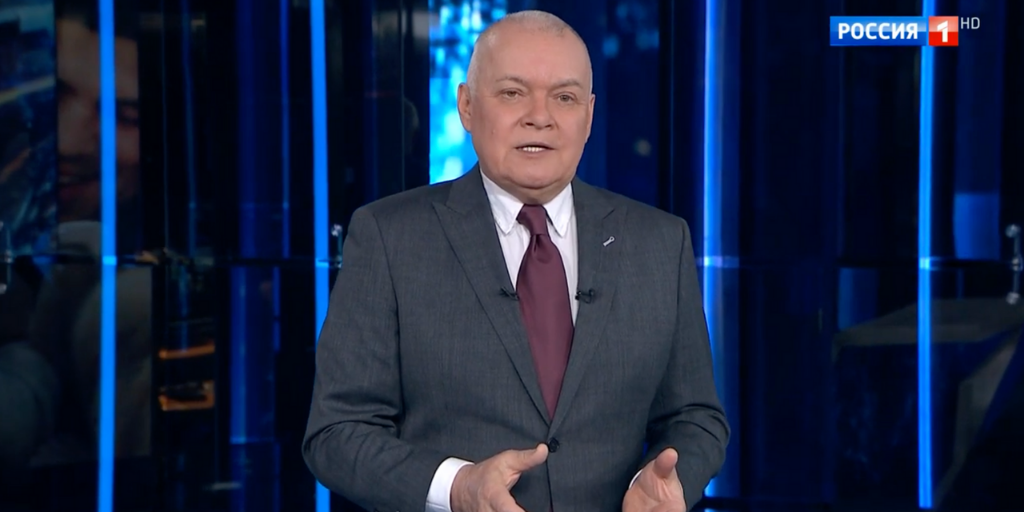

It is now five years since the EU began to introduce sanctions against individual key actors in Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. One of the names to appear on the EU’s lists was that of Dmitry Kiselyov.

Often nicknamed “the Kremlin’s chief propagandist,” this TV host and media manager was the only Russian journalist to face a personal EU sanction over the Ukraine conflict – a decision Mr Kiselyov later appealed against in the EU Court of Justice, but without success.

How did someone who had once been known as a defender of journalistic ethics and a friend of Europe, the US and Ukraine, become the embodiment of modern Russian state media control and a figurehead in media attacks on these foreign countries?

Two sides of the medal

Dmitry Kiselyov received his EU-sanction as a “central figure of the government propaganda supporting the deployment of Russian forces in Ukraine”.

The sanction identified Mr. Kiselyov’s role as particularly problematic among his peers. Until this day, it serves as a warning to other Russian state propagandists.

Dmitry Kiselyov’s Sunday night programme Vesti Nedeli (“News of the Week) on the state TV Channel Rossiya 1 has played a key role in the Kremlin’s disinformation campaign against Ukraine.

Dmitry Kiselyov’s Sunday night programme Vesti Nedeli (“News of the Week) on the state TV Channel Rossiya 1 has played a key role in the Kremlin’s disinformation campaign against Ukraine.

However, the sanction also expressed the EU’s acknowledgement that media communications is not only a tool of soft power; media is also something that can play an integrated role in the use of hard power, in coordination with real military aggression.

The Kremlin has also recognised Dmitry Kiselyov’s role by decorating him with “For Merit to the Fatherland” – an order awarded to Russian citizens for “outstanding contributions to the state.” The EU sanction can be seen as the flip side of this Russian recognition.

A friend of journalistic ethics and foreign countries

In the years leading up to Russia’s aggressive engagement in Ukraine, Dmitry Kiselyov was by many seen as a liberal and as a defender of free and independent journalism.

In an often-quoted statement from a 1999 TV discussion, Dmitry Kiselyov expressed concern with journalistic ethics

“A journalist cannot be separated from ethics. But the people you see on the screens can often not be called journalists, because often they are just agitators <…> The task of a journalist, in my opinion, is to show the correct proportions of the world, to show the whole picture of the world <…> With any lowering of the bar, any reduction in moral and rules, <…> we will find ourselves in mud, bathing like pigs. And there will be such a society. And we will be eating each other along with the dirt. That’s where we will find ourselves. And it will be impossible to descend any lower than that.”

Mr. Kiselyov lived in Europe for a number of years, working as a foreign correspondent. In the 1990s he received funding from the EU for producing a programme about Europe on Russian TV. In 2012, he travelled to the US on an invitation from the State Department. In addition, for a number of years in the early 2000s, his professional career was closely tied to media outlets in Russia’s neighbour country Ukraine.

Nuclear Ashes

The turning point in Dmitry Kiselyov’s career came when he in 2013 was appointed the CEO of the then new state media giant Rossiya Segodnya, which, even if it translates as “Russia Today” is formally a separate organisation from RT – although the two media organisations have the same chief editor, Margarita Simonyan.

Rossiya Segodnya includes the Russian news agency RIA Novosti; the international agency Sputnik, which spreads Russian state propaganda in over 30 languages; and the online platform INOSMI, which translates international press into Russian.

At the same time, Dmitry Kiselyov has been the host of his own weekly current affairs programme on the TV channel Rossiya 1, which is in turn a part of another state media giant VGTRK, where Mr. Kiselyov is also the deputy director general.

Dmitry Kiselyov’s weekly show on Rossiya 1 was where he talked about Russian being capable of turning the US into “radioactive ashes”; where he recently managed to lie at the speed of one lie per minute; and from which hundreds of cases of disinformation have been broadcast to Russian Sunday night audiences. Follow this link to see examples entered into the EUvsDisinfo database of pro-Kremlin disinformation.

Spreading disinformation with a speed of one lie per minute, Dmitry Kiselyov keeps living up to his reputation as one of the Kremlin’s most passionate propagandists.

Spreading disinformation with a speed of one lie per minute, Dmitry Kiselyov keeps living up to his reputation as one of the Kremlin’s most passionate propagandists.

“The period of impartial journalism is over. Objectivity is a myth”

Analysing what exactly made Dmitry Kiselyov change could easily become speculative.

One could perhaps assume that the Russian authorities’ call for loyalty epitomised in the famous slogan “Crimea is ours!” awakened a sense of patriotic duty in Mr. Kiselyov and forced him to side with the Kremlin’s highly controversial policies.

However, a speech Dmitry Kiselyov gave in 2013, when he took the seat of the CEO of Rossiya Segodnya, suggests that the turn not just about subordination to the Kremlin, but also a turn away from democracy: “The period of impartial journalism is over. Objectivity is a myth that we have been offered; it has been imposed on us,” Kiselyov announced to his staff.

This radical kind of perspectivism and the labelling of fundamental journalistic values as foreign and undesirable in Mr. Kiselyov’s programmatic address to his team challenge the notion of journalism as a truth-seeking and independent fourth pillar of power. Stripped of that societal function, the role of journalism in a democracy is weakened, and the value of democracy degrades.

Not just “fake news”

The speech by Mr Kiselyov serves as a reminder that the form of propaganda practiced by him and likeminded colleagues is not simply a case of spreading “fake news”; it is also more than simply a state’s strategic communications campaign with a license to lie.

Dmitry Kiselyov represents a form of communication which abandons democracy, loses faith in ethics and responsibility as key notions of journalistic professionalism.

What people like Dmitry Kiselyov can offer is a product, which on the surface might resemble journalism, but is rather a form of entertainment, which a government can intrumentalise in support of its policies, its wars; and importantly, it is a service that can help to keep a government in uninterrupted, continuous power.