Many commentators have discussed whether Vladimir Putin is a fascist in any serious sense, but most have failed to consider one area where fascism has clearly arisen in his Russia: in the aesthetics that increasingly inform Moscow’s public life and that have obvious parallels with those of the Third Reich, Innokenty Malkiel says.

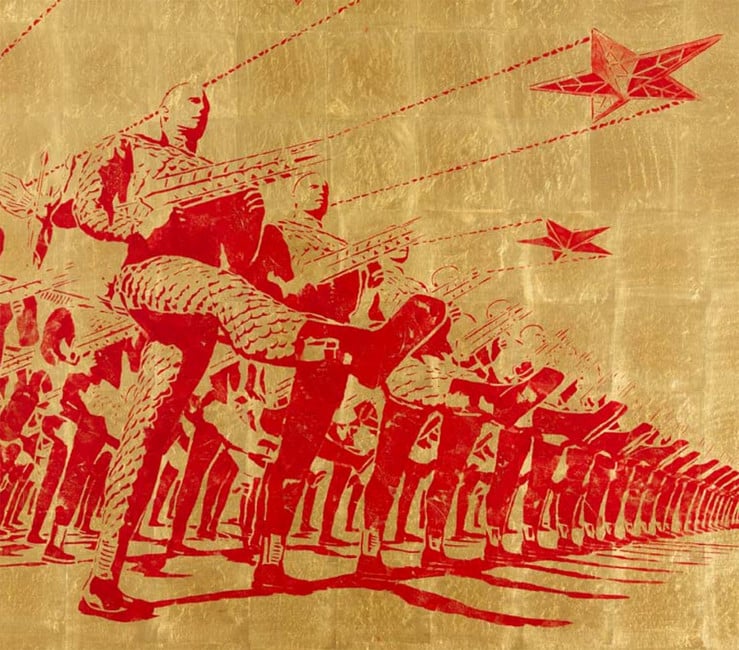

“The legions of tomorrow marching through Red Square are a multitude of strong young men lacking any individual characteristics,” the art specialist says in a commentary for Open Russia. “The monochromatic, red-gold or black-white, ascetic but at the same time monumental” reflect values “from ancient Egypt to Stalin’s times,” but they are now being presented not as something from history but “as a model for the future” (openrussia.org/notes/709612/).

“Masculinity, militarism, monumentalism, and an appeal to antiquity are all things we have already seen and not so long ago – all of 70 or 80 years ago in Nazi Germany.” And some things we see in Russia today “shock by their similarity (is this accidental?) with the forms of Albert Speer or Arno Brecher of that period,” Malkiel says.

In all too many cases, he continues, the fascist aesthetic of Leni Riefenstahl is present and “behind it stands a corresponding ideological basis.”

“At first glance,” Malkiel continues, “the ideology of ‘the Eurasian Movement’ is unlike the ideology of the NSDAP. However, when one talks about ‘a Eurasian Union’ on the space of the former USSR, the question arises: by what means will ‘the reunification’ of these territories be carried out?”

And when one asks that question, he says, “we see there populism and expansionism and ‘special path’ and militarism and extremism – that is, most of familiar aspects of fascism.”

Fifteen years ago, Eduard Limonov, then a comrade in arms to Aleksandr Dugin, praised the Eurasianist for being in the Russian context “’the Kirill and Methodius of fascism.’” Today, Malkiel says, “the catechism of a member of the Eurasian Youth Movement” does not leave any doubt about that.

“You must be a master,” that document reads. “You were born to rule Eurasia. You are more than a man. Our goal is absolute power. We are the Union of Lords, of the new overlords of Eurasia. We will turn everything back. Such is the white testament of Eurasia.”

Such attitudes have spread beyond politics, Malkiel continues. They are now informing the work of many Russian artists who say these are simply a matter of “the Russian style,” an indication of just how far they have spread into the popular culture and how much that style now simply represents a recrudescence of “a fascist aesthetic” in Putin’s Russia.

That is clearly seen in the posters Russian artists prepared for the Sochi Olympiad, which like their Nazi predecessors featured “’true Aryans, blond and blue eyes in front of buildings whose neo-classical architecture completely coincides with the style of the Third Reich.” It is impossible,” Malkiel continues, “not to see corresponding parallels.”

(His article is especially useful because it features pictures of this new art.)

Some Russian artists argue that they have the right to use fascist symbols because the Soviet Union defeated Nazi Germany and thus can appropriate its art, but “in fact,” they are using it in anything but a critical way but rather to promote a similar aesthetic and a similar political agenda.

And “present-day Russian ‘stormtrooper artists’ and ideologues of extreme right views with each year see ever more in Putin and his regime ‘a common spirit.’” Dugin is among them. Almost a decade ago, he said that Putin was “returning to us the symbols of the Soviet period and respect for it” and the need to exclude all Western influence on Russia.

Already at that time, he continues, “Dugin sensed the side to which the Russian powers that be were drifting. The events which have followed” have only encouraged “the ultra-right ideologues and artists” to conclude that he was right.

“Today we see,” Melkiel says, “how nostalgia for the Soviet empire is being reborn along with the aesthetics of that time, the aesthetics of Stalinism which in many of their manifestations are almost indistinguishable from the aesthetics of Nazism.” Indeed, it is “more correct to say that today we see their new birth in combination with each other.”

This trend, he suggests, is leading to “the complete political disorientation of the population” and thus making the rise of “ultra-right nationalism and the worldwide trend toward population” more likely and more dangerous.

“To let the fascist genie out of the bottle is easy, but to put it back is difficult,” the commentator says. “The last time this required tens of millions of lives. Given the existence of nuclear weapons, how many more might be required now?” And could it be that this aesthetic may lead some Russians to demand a fuehrer who would go even further than Putin has?

By Paul Goble, Window on Eurasia