By Paul Copeland

BEYOND PROPAGANDA | AUGUST 2016

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The age of information has mutated into the age of disinformation. Authoritarian rulers have learnt to

entrench their power by flooding societies with disinformation that divides, confuses, and intimidates

democratic opposition. Aggressive states and terrorist groups use mass-media falsifications, hate videos,

and social-media trolls to destabilise other countries and communities. Across the world the Internet and

global media have empowered conspiracy theorists and violent extremist groups have emerged from

the fringes to set the social agenda. In democratic societies we are seeing the emergence of a “post-fact”

politics where candidates reinvent reality at whim, making debate impossible.

A range of international bodies, from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

(OSCE) to NATO, have identified Media Literacy—the ability of audiences to think critically and

analyse the manipulative propaganda around them—as a key way to withstand information war, lies,

and hate speech. However, Media Literacy has always been associated with education in schools and

universities and to have real influence, it needs to be incorporated into mainstream entertainment

television and online products. To this end the following needs to happen:

» Media Literacy experts should unite with entertainment content creators to draw on the experience

they have in designing entertainment formats.

» Donors, development agencies, and international public-service broadcasters should mainstream

Media Literacy messages into the content they produce and support.

» Rather than a separate theme, media literacy needs to be integrated into mass-appeal formats

such as soap operas and chat shows.

» Different formats, genres, and media (TV, online, on-demand) should be used for different audiences.

This paper looks at what sort of formats could work in the Middle East and Ukraine, two areas that

are deeply affected by propaganda and information wars.

Formats that might be appropriate for mass audiences include:

Panel chat shows and breakfast shows

Typically, these are lively studio-based chat shows where a panel of hosts discuss topical matters

with celebrity guests. The Media Literacy “takeaway” would come in the form of light and

humorous discussions of the news of the day. If this kind of material is too emotionally divisive,

or if censorship is a big problem, such shows could use more “neutral” areas like entertainment or

celebrity news to teach Media Literacy. It is still possible to lay out the key points and encourage

critical thinking, even if the targets are celebrities and their PR managers rather than governments.

Celebrity travelogues

Such travelogues would feature popular presenters who would travel around the region, celebrating

its natural and cultural wonders. These shows could subtly explore Media Literacy principles, but they

should not be overtly political—they should be located in a space where contemporary politics do not

seem to intrude.

Soap operas, melodramas, and telenovelas

Media Literacy plot-lines could be introduced into story-lines—for example, in situations where

characters make good or bad decisions based on how they interpret media.

Talent shows

Talent shows such as The Voice are the biggest rating successes in both Ukraine and the Middle

East. Media Literacy principles could perhaps be introduced through, for example, a comedy

talent competition. Or use of a particular song could draw attention to the harm caused by hate

speech and propaganda.

Children’s TV drama

Such drama would allow Media Literacy to be considered in allegorical terms, moving the action

away from reality into a world of fable or fantasy.

Formats suitable for audiences better informed about current affairs include:

Satirical news review shows

The most obvious idea would be a satirical news show, or news review show, along the lines of

The Daily Show in the US.

Current affairs comedy quiz shows

A linked idea would be a satirical current affairs game show along the lines of the long-running

Have I Got News for You? in the UK.

Situation comedies

Another idea would be a satirical situation comedy (sitcom) set in a TV news outlet grappling

with the demands of censors and propagandists.

To boost the appeal of existing online fact-checking and counter-messaging sites, we recommend

the following:

Media Literacy online games

Online “Golden Raspberry Awards” for the “Top Ten Lies”

Targeted social-media analysis showing which disinformation stories are trending and

demand a response

As a next step, we propose a Media Literacy Entertainment Working Group bringing together educators

and entertainment producers to create pilot programmes based on these recommendations.

INTRODUCTION

In the video we see a man wearing a Guantanamo-style orange jumpsuit which marks him out as a prisoner. He is taken at gunpoint into a crude amphitheatre of rubble and shattered buildings, watched by scores of silent, masked men who train their weapons on him, ready to shoot. He lifts his eyes to the heavens, as if to acknowledge his guilt and ask God for forgiveness. Then a burst of stylish computer-generated effects—like something from a TV or movie trailer—takes us to flashbacks of what appears to be the same place on the night it was destroyed by bombs. The bombs, we are told, were dropped by the man in the orange jumpsuit. Injured children scream; medics work desperately; men and women are carried away on stretchers—we cannot tell whether they will live or die. The video makes us feel the man in the jumpsuit deserves punishment.

Then we are back in the present, in the broken amphitheatre of the bombsite. The man has been placed in a cage. The camera is close up on his young face: his mouth hangs open impassively, he is waiting and watching. So are we. The music has a slow, soft beat—like a heartbeat—building tension. On every heap of broken concrete and from every shattered window the masked men stand sentinel. There is something solemn and authoritative about them, as if they are here to watch justice being done—for the sake of the injured children, we are meant to think.

Another burst of computer-generated imagery leads to another flashback. We are shown the people behind the bombing this man has carried out: the kings of Saudi Arabia and Jordan, Obama, Bush, Netanyahu, the UN Security Council.

We return to the broken amphitheatre. The editing moves between the man and the sentinels. We cannot help but feel nervous and excited. One of the masked men steps forward and draws a flaming torch out of an oil drum. The heartbeat music stops. It is silent. The tension is excruciating. Islamic chant music begins, the masked man steps forward and lights a trail of fuel oil, which surges towards the cage …

I haven’t seen what happens next. I don’t want to. But this video of the execution of a downed Jordanian

pilot by ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) in 2015 is almost as shocking for its storytelling and

film-making brilliance as it is for its barbarity. (1) Watching it, you cannot help but have your emotions

manipulated. It plays on Muslim grievances about history and oppressive Arab governments in league

with Israel and the West.

I am a film-maker and television producer. I have long been fascinated by the power of the moving image and other media to affect our emotions and change the way we think. When I see propaganda like this ISIS video—in all its insidious brilliance—I want to know why the bad guys seem to tell the best stories.

And it is not just terrorist groups that are telling powerful stories to advance dubious aims. The Kremlin advances its strategic goals at home and abroad with a potent mix of conspiracies, scare stories, and disinformation.(2) In democracies “post-fact” politicians reinvent reality at whim and use emotionally manipulative narratives, falsehoods, and hate speech to advance their agendas.

Faced with this new era of propaganda and information war, institutions ranging from OSCE to NATO are calling for more Media Literacy as an antidote. Audiences need to learn to tell the difference between accurate, informational reporting and manipulative propaganda—to understand

the sources of messages they receive and the motives by which they are driven. But, as its name suggests, Media Literacy is traditionally seen as something that is taught at school, if it is taught at all—the kind of lesson that kids find boring but look forward to as they know it will be easy.(3)

But what if we used the skills of our best storytellers and creatives to make Media Literacy as popular

as the lies and propaganda with which it engages? What if we moved it out of the classroom and wove

it into the fabric of ratings-winning shows?

In the following pages I will survey the world of Media Literacy and seek to identify the best and most innovative practice. I will ask how the various media can be used more effectively, and how the most popular types of media content might be recast, to promote Media Literacy. And I will make practical suggestions for media projects to test the various ideas proposed in the paper.

1. UNDERSTANDING MEDIA LITERACY

WHAT IS MEDIA LITERACY?

The US National Association of Media Literacy Education (NAMLE) defines Media Literacy as follows:

Media literacy is the ability to access, analyse, evaluate, create, and act using all forms of communication. In its simplest terms, media literacy is an expansion of traditional literacy. Media

literacy empowers people to be critical thinkers, effective communicators, and active citizens.(4)

NAMLE’s link of Media Literacy to “traditional literacy” is indicative of the conventional link between

Media Literacy and education, and Media Literacy is indeed part of school life in many countries. In

the US nearly all 50 states have Media Literacy elements in the curriculum,(5) while in the UK Media

Literacy has been included in the National Curriculum since 1990 and is now part of the Citizenship

Programmes of Study.(6) In these and many other countries, it is seen as part of training young people

as democratic citizens so that they can better understand and analyse political discourse.(7) There is

also a big emphasis on helping children navigate consumer culture and advertising.(8)

In 2011, when UNESCO published a curriculum on the subject, they called it “Media and Information

Literacy Curriculum for Teachers”, dividing what NAMLE and many others call Media Literacy into

“Media Literacy” and “Information Literacy”:

On the one hand, Information Literacy emphasises the importance of access to information and the evaluation and ethical use of that information. On the other hand, Media Literacy emphasises the ability to understand media functions, evaluate how those functions are performed and to rationally engage with media for self-expression.(9)

I will, however, continue to use the term “Media Literacy” as it draws attention to the media at a time

when it is the increase in scope and intensity of media messaging that is heightening interest in this area. I would argue that Media Literacy should be shorn of the automatic link with education. Many of those most in need of Media Literacy are older people, and in regions rife with propaganda the situation is generally too pressing to wait for the next generation to learn Media Literacy and grow up.

It is, therefore, more useful to put emphasis on the “critical thinking” aspect of Media Literacy rather than on the “expansion of traditional literacy” aspect. Regardless of the ability to read and write, audiences need to think critically about how a TV programme is making them feel and think.

MEDIA LITERACY, MEDIA DIVERSITY, AND COUNTER-PROPAGANDA

As governments and intergovernmental organisations search for a response to the rise of sophisticated

propaganda and “information war”, more and more people are calling for increased Media Literacy.

For example, a 2015 OSCE report, “Propaganda and Freedom of the Media”, has among its key “tool

boxes” of response “Putting efforts into educational programmes on Media and Internet Literacy”;(10)

and a 2016 NATO Stratcom report on “Internet Trolling as a Tool of Hybrid Warfare” lists as a key

recommendation for governments “Enhance the public’s critical thinking and media literacy”.(11)

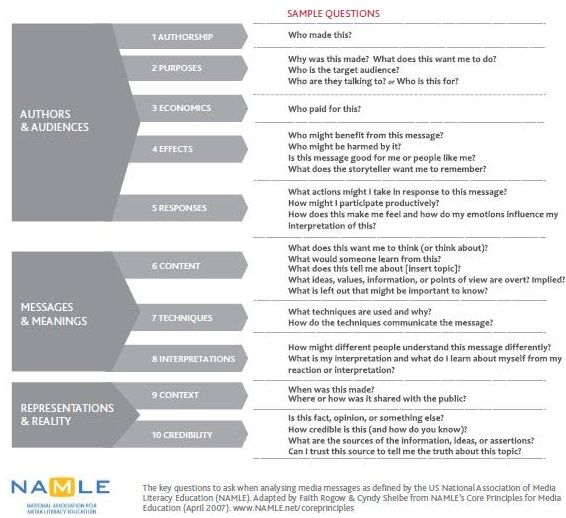

KEY QUESTIONS TO ASK WHEN ANALYSING MEDIA MESSAGES

USING THIS GRID—Media literate people routinely ASK QUESTIONS IN EVERY CATEGORY—the middle column—as they navigate the media world. Occasionally a category will not apply to a particular message, but in general, sophisticated “close reading” requires exploring the full range of issues covered

by the ten categories. The specific questions listed here are suggestions; you should adapt them or add your own to meet your students’ developmental level and learning goals. Encourage students to recognise that many questions will have more than one answer (which is why the categories are in plural

form). To help students develop the habit of giving evidence-based answers, nearly every question should be followed with a probe for evidence: HOW DO YOU KNOW? WHAT MAKES YOU SAY THAT? And remember that the ultimate goal is for students to learn to ask these questions for themselves.

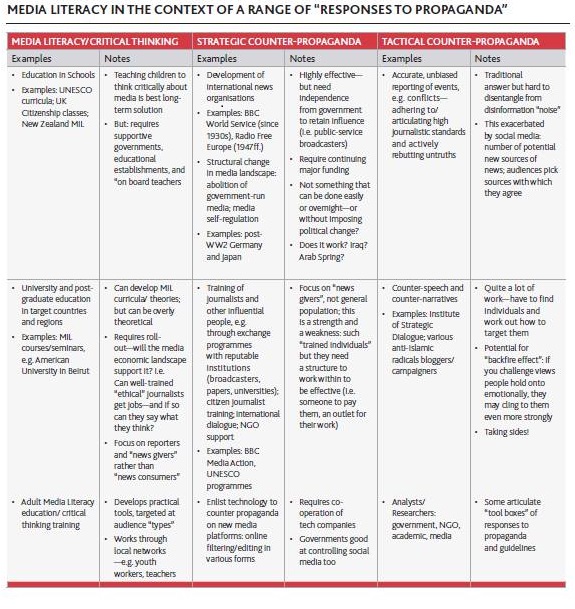

The table on page 9 places Media Literacy in the context of a range of “Responses to Propaganda”

that are commonly being discussed or undertaken. It draws a distinction between big-picture

“strategic” counter-propaganda initiatives and more immediate “tactical” responses to individual

propaganda campaigns, messages, or actors.

“Strategic” responses, such as setting up a news agency, tend to be hugely expensive and timeconsuming.

Various forms of journalist training are undeniably worthy efforts but fraught with

challenges; for example, where are these journalists going to get jobs, or platforms popular and

credible enough on which to distribute their “honest” content? “Tactical” responses are also fraught

with difficulty. Some work is being done in the field of counter-narratives, particularly with regard to

Islamic extremism. The counter-narrative projects of the Institute for Strategic Dialogue—which

include using former Islamic extremists to engage with potential new recruits to extremist groups—

are one example.(12) But when it comes to combating propaganda campaigns aimed at broad populations, it is obviously impractical to engage every individual in a one-to-one dialogue. Such campaigns also risk getting drowned out in all the information “noise”—including the deliberate spreading of fakes and falsehoods—with the result that audiences do not know what to think, decide everything is equally unreliable—and give up.

So if “counter-messaging” is not enough, we are left with helping audiences to listen better, to

analyse and evaluate messaging and information critically—in other words, Media Literacy. But to

have any chance of promoting Media Literacy beyond a small group of well-informed people who

are interested in it in the first place—and who are therefore probably sufficiently media-literate

not to need much training anyway—we need to do two things: to find ways to get Media Literacy

training messages out there in countries and regions; and to make it popular.

THE LATEST IN MEDIA LITERACY: US, MIDDLE EAST, AND UKRAINE

The concept of Media Literacy has long been seen as going hand in hand with education, but

what Media Literacy education means is changing. It is moving out of the classroom and into

communities; it is expanding from young people to audiences of all ages; and it is shifting from its

home in the West to other parts of the world, where the need is even greater. In all these contexts,

however, there are certain key lessons in common—lessons that Media Literacy teachers aim to

get across to their students in order to help them think critically about the media and which can be

taken and repackaged in new and popular ways.

Universities have done most to get the Media Literacy message out internationally. Many of the

longest-established and most respected centres for Media Literacy are in the US—among the most

notable is Stony Brook University, the State University of New York. Stony Brook’s Center for News

Literacy (another example of the slipperiness of terms in this area) describes itself as committed

to teaching 10,000 students “how to use critical thinking to judge the reliability and credibility

of news reports and news sources”.(13) The Center works closely with Stony Brook’s Department of

Political Science, a faculty which has broken new ground in bringing together political science and

psychology in order to understand how media messaging affects people and the way they vote.(14)

The Center for News Literacy organises its subject into key concepts, each embodied in a “Course

Pack” for students.(15) These include:

1. The power of information—including discussing how images and video are particularly powerful at moving audiences and inspiring change, and why a free press is important as a check on those in power.

2. Truth and verification: how (good) journalists weigh up probabilities and use evidence to verify.

3. What makes news different: how news needs to be held to a journalistic standard of verification.

4. Fairness and balance: being fair to all sides of a story, and the (blurry) line between news and opinion.

5. Bias: how to spot it, and how it exists not just in news providers but in audiences as well.

6. What is newsworthy: the “Universal Drivers” of news, and how news editors exercise editorial judgement.

7. Different types of media: established media, how search-engine rankings do not necessarily mean

that sites are the most reliable, the way misinformation can spread online.

The classes themselves combine lectures on theory with exercises using real-world case studies. For

example, the class on “Truth” and how journalists seek to establish it begins by talking about the

importance of sources; the more of them there are, the closer they are to having personally witnessed

the events in question, and the more closely they agree about what happened, the greater the weight

a journalist will place on their account. The class stresses that sometimes the truth will evolve as the

journalist discovers more and better sources, and therefore that the “media-literate” news consumer

will follow a story over time. It emphasises the importance of transparency (that journalists make clear

how they found out what they know and make clear what they don’t know) and context (that enough

information is given around a “fact” that we can understand its real meaning—its “truth”).

As the course unfolds, students become adept at applying the lessons they learned to the media

around them. In the class on “Fairness and balance” students are taught to look for “signs of opinion

journalism”: first-person declarations, exaggeration, emotionally loaded words, tone and parody in

news pieces. In exercises students are asked to consider what it means when a news anchor uses the word “terrorist” on air—and, applying the same critical process to another subject, to discuss

“Was Fox News crossing the line separating news from opinion when it began to refer to the [2013]

government shutdown as a “slimdown” on its website?”(16)

The Center doesn’t just seek to serve its students; it makes a great deal of learning material available

on its website. This hosts collections of online lessons, including ones that apply to topical subjects

such as the 2016 presidential campaign—for example, “Why Donald Trump is Big News”.(17) This

lesson explains the media attention on Trump—and the free airtime lavished on his campaign—in

terms of “tried and tested news literacy concepts”. These include “10 Universal News Drivers”,

defined as “common attributes of news stories through recorded history in every society”, all of

which can be identified as at work with Trump:

1. Prominence: it is news because the person involved is already a celebrity—Trump is a famous

businessman and reality TV star.

2. Importance: the topic has big implications—he is running for president.

3. Human interest: Trump has a rich and glitzy lifestyle.

4. Conflict: Trump attacks and insults everyone and that is engaging to follow.

5. Change: Trump promises to change America—and he has already changed the Republican Party.

6. Unusualness: he is not like the other runners or what has gone before.

7. Proximity: it is close to home—he is in America and in almost every state.

8. Timeliness: the campaign calendar, debates, primaries, caucuses.

9. Magnitude: there are a lot of stories about him.

10. Relevance: the story hits home for Americans whether in a good way or a bad way.

The lesson shows how these “drivers” interplay with news editors’ editorial judgement—and their desire to make news “entertaining” and win audiences—to keep Trump in the limelight. The effect on anyone taking the lesson (at the university or online) is to make them think critically not just about Trump and how he is operating, but about the media itself, the way it works, and the impact of this on the information we as audiences consume.

Stony Brook runs a five-week online course run by the University of Hong Kong’s Journalism and

Media Studies Centre,(18) with which Stony Brook has also developed Asia-focused curricula.19 The

Center for News Literacy has also forged partnerships with universities in Russia, China, Poland,

Vietnam, Malaysia, Bhutan, and Hong Kong.

These efforts exemplify a gradual process by which Media Literacy education is spreading from

its “home” in the West to other regions and countries, and from formal academia to semi-formal

educational contexts. Another notable example is the Salzburg Academy on Media and Global

Change, a partnership between the University of Maryland and the Salzburg Global Seminar (an

NGO) which brings together students and teachers from around the world.(20) The idea behind the

Academy, as Dr Jad Melki of the Lebanese American University and one of its leading lights put it,

“is that they’ll go home and pass on their training to others”.(21)

Dr Melki is probably the Arab world’s leading Media Literacy pioneer. He received his PhD at the

University of Maryland before returning to Lebanon in 2009, where he found that he was “pretty

much the only person doing anything on Media Literacy in the entire Middle East”. He instituted the

first Media Literacy courses in universities in the region, and looked to find ways to roll out Media

Literacy teaching through other universities, colleges, and schools. He found there were “three big

problems: no curricula in Arabic; nothing catering to the Arab region; and no qualified teachers”.

Dr Melki’s solution was the Media and Digital Literacy Academy of Beirut (MDLAB), established in

2013 with support from the Open Society Foundation.22 MDLAB aspires to be a regional hub for

Media Literacy, to which undergraduate and graduate students, academics, teachers, and activists

from around the region can come for courses. The idea is that they then take that knowledge home,

spreading it throughout Arab universities and more broadly in society.(23)

MDLAB offers a Stony Brook-style academic Media Literacy course tailored to the Arab world; it is

available bilingually in English and Arabic—English remains important, MDLAB says, because it is

the dominant language of so much media. As with other courses, Media Literacy at MDLAB involves

learning to interrogate the media, asking such questions as: what information a media message

contains and what it omits; how it is constructed to work on the audience; what values and points

of view it embodies; who has created it and for what purpose.(24) For example, the course begins with

deconstructing an advertisement.(25) What is the advertisement trying to sell? Does it work through the

emotions or through information? Does it promote a particular lifestyle or socioeconomic group?

MDLAB’s focus quickly shifts onto the role that the media play in the region’s political and religious

upheavals. As Dr Melki puts it, “One of the things that really differentiates Arab MDL [Media and

Digital Literacy] is the need to talk about conflict.” The foundation course syllabus includes a

module on “Media and Sectarianism”, where students have to write an essay “about how media has

contributed to sectarianism in your news stories [i.e. stories produced locally in participants’ home

countries] and what modifications were necessary to avoid it”.(26) There are also modules applying

social-science concepts such as “framing” to topical news stories and images. Framing analyses the

way media material is organised and presented to draw the audience’s attention, and the context in

which the audience interprets the message.27 For example, there are a number of different frames that

the media could give to an image of a Palestinian boy throwing a stone at an Israeli tank.

The exercise “Propaganda Tactics” identifies markers to watch out for in media messages:(28)

» Contextualisation: placing together of unrelated images or ideas to force an emotional or intellectual connection. This may cause the transfer of emotions from one scene to another.

» Us-versus-them manipulation: or ingroup/outgroup manipulation, where you distinguish a group (by visual indicators) as inferior and identify yourself and the audience with the superior group.

» “FUD-ing”: spreading Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt about a person’s motives, usually by showing the

person’s actions as motivated by selfish ends.

» Traps: embarrassing a target, with personal attacks or showing them as foolish, when such

embarrassment has little to do with the person’s position.

» Manipulating cause and effect: playing on an audience’s tendency to believe that correlation implies causation AND emphasising simple, singular causes.

» Modelling: showing viewers behaviour that the propagandist wants them to emulate, often in a

positive light.

» (Modelling) conversion: showing viewers people who have reformed themselves by rejecting their

previous “negative” behaviour.

» Pacing and distraction: diverting viewers’ attention from the limitations of an argument by speeding the pace and adding audiovisual distractions, and slowing when the argument is strong.

» Numeric deceptions: employing numbers deceptively to imply solid evidence for an argument, knowing that most people will not check the numbers.

» Shutting down the opposition: using various tactics to forestall or block opposing voices from challenging the arguments, by excluding these voices or pre-emptively attacking and threatening them to keep silent.

It is easy to imagine how such a list could be turned into an exercise, game, or quiz which anybody

could use to get wiser about propaganda, and it points the way to the next step in getting Media

Literacy out to the people who need it most.

In Ukraine the International Research and Exchanges Board—or IREX, a Washington DC-based global

non-profit “providing thought leadership and innovative programs to promote positive lasting change

globally”—has stepped outside the education system to promote Media Literacy.(29) IREX’s Citizen

Media Literacy Project—supported by the Canadian government’s Department for Global Affairs—ran

courses during 2015–16 which used its own parallel educational network of “trainers” built up over

the years of the NGO’s involvement in Ukraine on such projects as support for community libraries.

These trainers, numbering more than 440 and located in the centre and east of the country (including

places in or near conflict zones), were charged to deliver IREX’s Media Literacy Curriculum to as many

people from all walks of life as they could persuade to sign up. The curriculum itself is an impressive

document largely developed from scratch by a team led by IREX Ukraine’s Director of Programmes,

Mehri Karyagdyyeva. In contrast to most Media Literacy curricula, it is meant to be both fun and full

of practical tools which anybody—with or without higher educational qualifications—can take and

apply to the media they consume. “We basically tried to get away from anything academic,” says

Karyagdyyeva, “rather developing practical tools targeted at different types of people so that the next

time they have an emotional reaction to a piece of ‘news’ or other media, they take a step back.”(30)

The curriculum is distributed to trainers together with a flash drive packed full of videos, games,

and props such as cards and stickers. The trainers then enrol as many as they can persuade into a

two-day course. The classes are carefully constructed to mix group exercises and games together

with mini-lectures that give a mass of information about media generally and Ukrainian media in

particular. Exercises include watching YouTube videos and identifying which ones are propaganda

and why, by asking questions which tease out “practical markers” such as lack of sources, strong

emotional appeal, and one-sided arguments. There are also quiz games that involve spotting fake

headlines and photoshopped pictures. Lectures are given on the Ukrainian media business and who

owns each TV channel. Participants are encouraged to think about where they get their news on a

typical day—what sources or channels—and to visualise this as a “personal media field” (i.e. a little

person with a web of media around). Fun games include distinguishing fake headlines from real

ones, showing how hard they can be to tell apart and indicating the kind of questions that need to

be asked to find out. In another exercise, participants imagine creating a fake news story (for a full

breakdown of the course, see the Annex at the end of this paper).

By the time the project came to an end in March 2016, 14,803 people had taken part. Of these

79 percent were women, 31 percent men, and 79 percent had some kind of higher educational

qualification. This was a more female and better-educated demographic than IREX had ideally hoped

for: anecdotally, it seems that because most of the trainers in the IREX network were teachers,

librarians, or university lecturers, they recruited the kind of people they knew. But it should be noted

that police and military officers, doctors, nurses, and journalists also took part in the training.(31)

There are some advantages in that the people trained by IREX are likely to have influence in their

home communities, but the demographic reached still falls short of truly “Making Media Literacy

Popular”. Karyagdyyeva is therefore thinking about ways the media itself could be used to carry

Media Literacy training direct to larger numbers of people. Specifically, an online game “teaching”

Media Literacy is in development. If Media Literacy is to become popular, it needs to stay fun and

appealing for people who are not necessarily interested in the first place.

The next stage in the roll-out of Media Literacy is to use the media itself to spread the message—

and in a way that draws upon the skills of content producers who know how to win (and keep) a

mass audience. This is the final stage of Media Literacy’s journey from the classroom and university

lecture hall into the public domain. It also involves turning the tables on the propagandists by taking

a leaf out of their book; if they have used the storytelling techniques of TV, online, and other mass

media to make their messages cut through, then surely we can too?

2. CASES STUDIES: MIDDLE EAST AND UKRAINE

Of all the ways to reach a mass audience, the two most powerful are undoubtedly TV and online.

That is not to say that other forms of media are irrelevant (for instance, IREX is using billboard

advertising to promote Media Literacy in Ukraine), but TV is still the world’s most popular and

widespread medium, as well as arguably the one capable of making the most emotional impact; and

online is the most dynamic and fastest-growing medium, and has the lowest costs of transmission.

Historically, TV has been used successfully to bring about important social change. Most famous

was Mexican TV producer Miguel Sabido, who created telenovelas with carefully designed plot-lines

about the need for family planning, helping to reduce the population growth rate in the country by

34 percent between 1977 to 1986. The Sabido methodology is now used across the world to help

deal with such issues as HIV.(32)

I will argue that Media Literacy can also make for good TV and online content. It is not a matter of

relying solely on the audience’s desire to learn or be informed—there will be plenty of opportunity

for humour, fun, liveliness, and other aspects that audiences enjoy. The remit that the BBC was

originally given—to “inform, educate and entertain”—is pertinent here.

As any international TV executive will tell you, what actually “works” for audiences varies widely

between and within different parts of the world. My focus in this paper is on the Middle East and

the former Soviet Union, specifically Ukraine. The types of content that are currently popular are

described; consideration is then given to the ways these might be reworked to carry Media Literacy

content. These two geographical areas share some key similarities. In both regions much of the

media is owned by business-political power players, who often run their media at a loss and with

low journalistic standards, and use disinformation to pursue their own interests. And in both regions

media is used to fuel divisions, hatred, and war.

THE MIDDLE EAST

The Middle East shows that both traditional TV and online platforms need to be considered when it

comes to promoting Media Literacy.

TV is king—people in the Middle East watch more TV than people in any other part of the world:(33)

4.39 hours per day in 2013 (a comparative figure for Europe is just under 4 hours),(34) and 96 percent

of people have access to a TV set. This means that at any one time across the day an average of 74

million pairs of eyeballs are glued to a set.

Internet penetration stands at 52.2 percent of the region’s population, but this masks a wide variation

between countries:(35) the richer nations have very high levels of internet use (Bahrain is at 91

percent, UAE 90.4 percent), while just 28.1 percent of Syrians, 22.6 percent of Yemenis, and 11.3

percent of Iraqis accessed the Internet during 2014.36 Interestingly, the 64 percent of Saudis who

access the Internet are proportionally the world’s most active users of Twitter, while the popularity

of other social-media sites including Facebook is considerably higher in the country than the world average.(37) Anecdotally, Saudis find social-media channels a useful way around the country’s strict laws: women use Instagram, for instance, to launch their own micro-businesses. Social media is

clearly important, therefore, but if we want to reach people in these poor and war-torn states where

terrorism is most active, we need to look at television too.

To gauge what is popular on TV, only the UAE, Lebanon, and Israel have automated TV-ratings

meter systems, but the market-research company Ipsos MORI is pushing into the rest of the region

with phone-based polling on an intermittent, monthly basis. This reveals some fascinating nuggets

about what some of these “offline” populations are watching while violence rages around them in the

country.(38) In Iraq, for instance, the most popular programme in November 2015 was the reality talent

show The Voice, which is broadcast on the pan-Arab satellite channel MBC. Next in popularity is

the Al-Iraqiya news programme, followed by two dramas, also on Al-Iraqiya. They are both Iranian produced and have religious themes: Mariam al-Moqadasa is about the Virgin Mary; the other is

about the early Shia Islamic Mukhtar al-Taqifa, who led an uprising against the (Sunni) Ummayyad

caliphs in Iraq in the seventh century (a period of history that reflects Iraq’s current sectarianism).

Then MBC appears again with a couple of popular, pan-Arab telenovelas—Zahrat at Qasr and Sharea

al Salam—and then its own (to some extent Saudi-focused) news show.

One interesting point about the top programmes list is how Al-Iraqiya is having success with more

explicitly political and religious shows which appeal to the country’s newly empowered Shia majority.

MBC’s output, on the other hand, looks more like TV fare as it is found in the rest of the world.

In Saudi Arabia MBC had all the top TV programmes during December 2015. The Voice was again

top, followed by a soap opera, a magician’s entertainment show, and a talk show. This feels like

Western TV as it was 20 years ago—a mix of glossy studio entertainment, game shows, talk shows,

popular melodrama, and soap. Conspicuous by their absence are satirical comedy, social or domestic

factual formats (e.g. cooking competitions), and “serious” documentary.

The Voice is currently the world’s biggest international entertainment juggernaut—it appears in the

top rankings of no fewer than 15 countries—but in the Middle East the show has been laced with

powerful political messages. Produced in Lebanon by a UK-owned production company (Talpa Media)

and broadcast from Dubai by a satellite channel owned by a Saudi billionaire (MBC), The Voice made

front-page news across the region when a nine-year-old Syrian girl, a refugee in Lebanon, burst into

tears while singing a traditional patriotic song, “Give Us Our Childhood” (the YouTube clip has more

the 40 million views).(39) As a political message this may not be as sophisticated as promoting Media

Literacy, but the casting of the Syrian girl and the choice of song were of course intended by producers

to provoke debate across the region. It is yet another example of the immense power of popular TV if it

can only be harnessed.

In Egypt, meanwhile, the ratings list is topped by a studio comedy, Masrah Masr, which (gently)

takes on subjects such as love and relationships. It is transmitted by MBC on a separate channel

(MBC Masr) dedicated to Egyptian tastes.

Another example of the satellite “broadcasting in” type is the Persian-language Marjan TV Network,

which broadcasts from London into Iran.(40) It serves up a mixture of syndicated Western shows

(Downton Abbey, Law and Order) and its own versions of established international TV formats, some

of which combine entertainment with political or satirical goals. For example, on its main channel

Manoto 1, Marjan broadcasts a Persian version of the UK-originated global format Come Dine with Me, where deliberately mismatched contestants compete to host the best dinner party for the others. They also broadcast Shabake Nim, a satirical puppet show derived from the 1980s UK hit Spitting Image,(41) and Samte No, an all-female panel show which discusses a mixture of everyday and more controversial topics.(42) Marjan claims that its Manoto 1 channel is the most popular satellite network in Iran, reaching over 23 million viewers.

(Courtesy of http://www.mbc.net)

Marjan is an example of how popular TV formats can be retooled to bring overtly liberal and political messages into restrictive societies (apart from anything else, the female hosts on Samte No do not have their heads covered). The GCC (Gulf Co-operation Council) countries—Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—show a greater conservatism in their viewing habits. As one producer put it to me, “nobody will watch Come Dine with Me in Saudi Arabia because you’d never invite male and

female strangers into your house and cook for them.”

In Egypt the satellite broadcaster Alhurra also experiments with politicised formats.(43) It is based in the United States and funded by the US Congress via the Broadcasting Board of Governors, which acts as a firewall from political interference, and the non-profit corporation Middle East Broadcasting Networks.(44) One of its most provocative series is Rayheen ala Feen (Where Are We Going?), a hard-hitting social documentary series following five young Egyptians as their lives were changed in the aftermath of the Arab Spring; it was unflinching in a way that is familiar in the West but extraordinary in the Arab world. One of its original cast of six—a member of Egypt’s conservative Salafist movement—was fatally shot during a protest rally on the night in July 2013 that President Mohamed Morsi was ousted by the military.(45) The show told what had happened and then continued with the remaining cast. Alhurra also broadcast the online documentary project Syrian Stories, following six individuals through Syria’s civil war. Like Marjan—and, in a more oblique manner, The Voice—these projects offer a fascinating model of how popular TV content can be laced with political meaning.

The Middle East and North Africa is the second-biggest market for YouTube viewership, according

to the Wall Street Journal.(46) Content could be shown on a TV channel, with a link back to YouTube

for further training and information. According to a 2014 study by the Mohammed Bin Rashid

School of Government in Dubai, Arab-speakers who are Internet-connected are keen users of online

education: 45 percent say they use educational blogs at least once a day, and 32 percent take free

online courses.(47) Perhaps less surprisingly, 49 percent watch video clips and 25 percent play online

games at least once a day.(48) As elsewhere in the world, TV is moving online: MBC and all the other

leading regional broadcasters offer their free-to-air content on demand over the Internet. There is

also a dynamic and highly fragmented market in video on demand (VOD), with Netflix and others

competing with regional players in both English and Arabic programming (the on-demand market is

concentrated in those richer countries where Internet penetration is high).

To conclude, in the Middle East:

» With respect to Media Literacy, on “mainstream” TV channels it is clear that light entertainment

is the most useful area to prioritise, as it delivers the biggest audiences while remaining non-contentious. Studio-based talk shows and panel shows are consistently high up in the ratings and offer plenty of opportunity for Media Literacy content.

» The biggest audiences go to spectacular studio shows like The Voice, so we should be alive to ways in which Media Literacy content could be placed in them.

» Soap, telenovelas, and comedy drama are also popular and might offer an opportunity to slide in

Media Literacy content without upsetting audiences or censors.

» For cultural reasons there is little audience appetite for factual formats or documentary—they

exist only on outside “broadcasters in” like Alhurra—so we should steer clear of these if we want

to use leading TV channels.

» The only exception to this may be programmes that warmly celebrate culture or history—if this

can be done in a way that spans the region and brings people together.

» We should give equal weight to online delivery and TV, using the regional appetite for online

learning and games to deliver Media Literacy content.

UKRAINE

Internet penetration in Ukraine is estimated at 43.4 percent,(49) one of the lowest in the region. In

common with much of the world, Ukrainian Internet users tend to be younger and better educated,

while the older generation rely on TV,(50) making it by far the most popular and important medium:

over 95 percent of Ukraine’s 45 million citizens watch television for an average of 3.32 hours per day

(this has declined since 2012 but is still up on 2011).(51)

Despite the ban on Russian broadcasters, a 2014 report commissioned by the NGO Telekritika

estimated that 63 per cent of the audience (including the war-torn far east of the country) can watch

at least one Russian channel, mostly via satellite or cable,(52) and about a third of respondents get their

news from Russian TV sources.

Ukrainian TV networks (the biggest of which are Inter, 1+1, Channel Ukraine, and STB) are loss-making,

oligarch-owned, and, according to Telekritika, inaccurate, fail to separate facts from opinion, privilege

official government sources over independent ones, and lack context and input from independent

experts.(53) As Telekritika characterise the reporting of the war in the east: “The Ukrainian media …

do not reflect the real picture in Eastern Ukraine. This has led them to be repulsed by locals in the

Donbas.”(54) On the pro-Russian side, opinions closely follow the line coming out of Russian TV. For

example, when the Levada Centre polled 1,500 ethnic Russians living in Ukraine as to who was to

blame for the downing of Malaysia Airlines MH17, 81 percent of respondents laid the blame on the

Ukrainian military, in spite of the overwhelming evidence that it was caused by a missile fired from

separatist-controlled territory.(55)

So Ukraine sits squarely in the front line of the 21st-century propaganda onslaught—a fact that

explains why organisations like Telekritika and IREX are so interested in Media Literacy.

Ukraine has a ratings meter system for terrestrial TV, the results of which are regularly published

online.(56) For January 2016 the top ten programmes were:

1. TSN (news programme, 1+1)

2. I Can Do Everything for Love (telenovela, Inter)

3. Stairs to Heaven (telenovela, Channel Ukraine)

4. Home Alone 2 (movie)

5. Home Alone (movie)

6. Unlucky Daughter-In-Law (movie, Channel Ukraine)

7. The Day Will Be Bright (movie, Channel Ukraine)

8. Podrobnosti (news programme, Inter)

9. Home Alone 3 (movie)

10. Family’s Best Friend (movie, Channel Ukraine)

That makes two news programmes, two soaps, and the rest movies.

http://www.stopfake.org/en/news/

Apart from the remarkable hold that films about American kids left at home to battle burglars seems to have over Ukrainians (could one theorise that they like escapist myths where the little guy trounces the big bad guys?), we can see that Ukrainians like comedy drama and soap over factual formats or studio-based entertainment (in contrast to the Middle East, where studio entertainment formats are much more dominant). There is also further evidence that they are turning to TV in large numbers to find

out about the upheavals in their country.

When we take into account the weaknesses in Ukrainian TV news coverage on all sides noted above, and the lack of trust in media across the board that these have engendered, it suggests a widespread appetite for better media information sources. And—in a small and fragmentary way—this is what is starting to happen. Hromadske TV is an Internet-based channel set up in 2013 as a response to the tightening censorship exercised by the government of then president Viktor Yanukovitch. The channel has a “minimalist” approach with a simple studio and little editing of its news footage, and it covers news from the region as well as from Ukraine. It has also experimented with hard-hitting real-life documentaries of the type conspicuously absent from the rest of Ukrainian TV (and indeed TV in Russia and most of the rest of the post-Soviet sphere). Now the YouTube Channel has 329,000 subscribers and its website claims up to 220,000 daily unique visitors.(57)

Another website set up in response to the conflict and its concurrent propaganda onslaught is

StopFake.org. It has built up a broad audience inside and outside Ukraine. An English-language

version concentrates on debunking false claims made by RT, Russia’s English-language news outlet.

Within three months of launching, the site had over 1.5 million unique users per month and 60,000

social-media followers. It is audience-financed via direct donations and crowd-funding. Significantly,

about a quarter of its users are from inside Russia, indicating a desire for independent news there too.(58)

Impressive as these figures may seem, they are of course small numbers next to those clocked up by

TV or by the big websites—the Russian social-media site VK (VKontakte), highlighted by the NGO

Telekritika for “spreading the same myths and stereotypes that the Russian propaganda creates”,(59)

has over 11 million unique users.(60) To some extent these websites must also be preaching to the

converted: if you access a site called StopFake.org, you are likely to have an awareness that you may

be exposed to propaganda. Moreover, the approximately 50 percent of the population who are not

online will contain many of the older people brought up in the Soviet Union who are most in need of

Media Literacy.

There is potential to reach out to a broader audience through the First National Channel. The reformed

public broadcaster has a relatively small audience share of just 2.1 percent,(61) but it is looking to

reinvent itself and has produced current affairs shows in partnership with Radio Free Europe, as well as

a youth drama series about the war with Russia in collaboration with BBC Media Action.(62)

To conclude, in Ukraine:

» The most popular formats are comedy drama, telenovelas, and soaps, so these would be a really

effective way to reach a Ukrainian audience. Escapist material seems to do best—soap, comedy,

or fantasy—though there may also be an appetite for satire.

» There is also a very keen interest in news and current affairs, and a paucity of reliable content.

With respect to Media Literacy, the best way to approach this might be to work through the “freer”

channels to bring topical news review shows which take the kind of Media Literacy-relevant work of

outlets such as StopFake.org or Hromadske to a larger audience in an amusing way.

3. MEDIA LITERACY: ON AIR AND ONLINE

In this section I will suggest some guidelines for getting popular Media Literacy content out on

media, and then some more specific ideas for content for TV or online.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

Several overarching principles inform our recommendations:

» Educators and entertainers must unite and work together. If Media Literacy is to be made truly

popular, Media Literacy experts need to unite with entertainment content creators to draw on

their experience in designing formats to carry “useful” public-service messages which can appeal

to audiences both locally and around the world. British producers have worked for broadcasters

such as the BBC and Channel 4, whose remit is to both inform and entertain, so they offer the

right skill set to tap into.

» Donors, development agencies, and international public-service broadcasters such as the BBC

World Service need to mainstream Media Literacy into the content they produce and support.

Consider the following situation. In Ukraine and other Eastern European states with large Russian

populations, broadcasters have requested Western donors’ help in creating native content. To

help with this, the UK is developing a “content factory” for Russian-language broadcasters; Radio

Free Europe is setting up a Russian-language satellite channel; the US State Department has

issued a tender to create “infotainment” for Eurasia. Such initiatives should include popularising

Media Literacy as a core ingredient.

» It is better to change people’s thinking habits than to overload them with information. At its

heart, Media Literacy is about asking questions of media—critical thinking—and that is a habit

of mind as much as a framework of knowledge. It can be delivered in small doses, wrapped up in

jokes or witty asides, and in this way change the way people think—this is more effective than

filling their heads with large amounts of detailed information.

» Different approaches and different content need to be used for different outlets, platforms,

audiences, and regions. Established TV channels and new “insurgent” broadcasters—websites

and social media as well as video-on-demand (VOD) broadcasters in the mould of Netflix. This

process is entirely familiar to content-creators the world over: the same idea is recast depending

on which broadcaster one is pitching to, and a particular subject will be tailored to the audience

you are trying to interest. This kind of mix-and-match approach can be followed without diluting

the core Media Literacy messages we are seeking to promote.

Bearing these key principles in mind, we can identify some characteristics popular Media Literacy

content is likely to possess.

First, as subject areas go, Media Literacy is pretty easy to make entertaining. It is naturally linked to

comedy and satire as it is in large part about debunking lies and exaggerations while sending up the

perpetrators, so a lot of the best Media Literacy ideas will (at least partly) be comedy.

Another quality essential for making Media Literacy content popular will be keeping it timely—it

needs to respond to news, current affairs, propaganda, and social issues. Otherwise, audiences will

not feel that it is relevant or that it speaks to them.

Thirdly, because Media Literacy is a matter of learning to ask the same kind of questions about all

sorts of different types of media, the content will have to be quite wide-ranging: this points towards

“magazine” or panel-show formats which are typically cheap to make.

Fourthly, although humour is probably the first weapon in the Media Literacy armoury, we can also

call upon other ways in which content draws in its audience: by engaging them in a human story, or

by exciting, moving, or frightening them. This opens up intriguing—and ambitious—possibilities in

the realms of drama and verity documentary.

These points will probably apply to different types of content on many different types of platforms

and outlets. But the content ideas themselves, and how they are produced, will vary: different

outlets will have different audiences, regulations, and political or social pressures, and different

financial and funding propositions will be required. I split these into three broad categories:

» Established networks broadcasting to mass audiences: the big, popular TV networks in their

regions, such as MBC in the Middle East and the oligarch-controlled networks in Ukraine.

» Insurgent networks catering for a more informed audience: smaller or more niche TV stations,

such as Hromadske in Ukraine and those broadcasting via the Internet.

» New media including websites, video bloggers, and any person or smaller organisation which

seeks to reach a large audience online.

CONTENT IDEAS

Established Networks

Working through large broadcasters offers the biggest prize in terms of audience reach and influence,

and hence of counteracting the impact of propaganda where it is needed most.

The trick will be to “slip” Media Literacy content into popular packaging while still taking account of

the political, social, and financial pressures under which the broadcaster operates. There might also

be a scenario in which an idea can be developed if those seeking to promote Media Literacy provide

part-funding for the show in exchange for a certain amount of Media Literacy content.

Panel chat shows and breakfast shows

One idea that could easily be tried in both the Middle East and Ukraine would be a topical panel

chat show—a lively studio-based show (morning, daytime, or evening) in which a panel of hosts

discuss topical matters with selected studio guests. This kind of format has the advantage of being

inherently topical, comedic, and cheap to make.

Such a show would probably include subsections on matters of interest to the audience—for example,

on cooking (“recipe of the day”) or entertainment and culture reviews. The Media Literacy “takeaway”

would come in the form of critical, but to all appearances light and humorous, discussions of the

news of the day. The presenters would just need to make sure that they regularly “hit” Media Literacy

principles along the lines of the key concepts included in the “Course Pack” issued to students by the

Stony Brook Center for News Literacy. Using the panel format, one presenter could give a “government

line” on something and another could—in an amusing and friendly way—challenge them and call out

the propaganda.

If this approach is too emotionally divisive or if censorship is a big problem, the show could use

more “neutral” areas such as entertainment or celebrity news to teach Media Literacy: the key

points can still be laid out, and critical thinking encouraged, even if the target is celebrities and their

PR managers (experts in propaganda!) rather than governments. Being light and apolitical, this will

seem less threatening and divisive, but it will still instil the critical thinking necessary to handle

overtly political disinformation.

Celebrity travelogues

An established network, having bigger budgets, also opens up the possibility of attempting more

ambitious formats. One to consider is the celebrity travelogue (in UK terms, think BBC1 or ITV

Sunday night with Michael Palin or Stephen Fry) in which a popular and safe presenter travels

around the network’s region, celebrating its natural and cultural wonders and meeting people. As

we can see from the ratings, history programmes are popular in the Middle East. In Ukraine they

can be very divisive if they are about their own region, though they might work if they focused

on faraway places (Ukraine could learn much from deeply divided Spanish history, for example).

Such travelogues should not be overtly political—indeed, they would ideally be located in a space

where contemporary politics does not seem to intrude—but they could still subtly explore Media

Literacy principles: for example, different interpretations of the same historical event from different

perspectives could be weighed and balanced.

Soap operas, melodramas, and telenovelas

Soap operas remain popular in both the Middle East and Ukraine, especially among older generations

and some of the least educated people. Media Literacy plot-lines could be gently introduced into

story-lines—for example, in situations in which characters make good or bad decisions based on

how they interpret media. A more radical solution would be to set a soap or melodrama around a

newsroom or PR agency, though that might appeal more to sophisticated viewers.

Talent shows

Spectacular talent shows such as The Voice are the biggest rating successes in both Ukraine and the

Middle East. The case of the young Syrian girl who sang a patriotic song prompted by the Syrian

war shows how a political context can be illuminated. Media Literacy principles might perhaps be

introduced through a comedy talent competition, for instance. Or a song might be used to bring

attention to the harm caused by hate speech and propaganda.

Children’s drama

Another interesting and ambitious area to consider for Media Literacy would be children’s TV drama.

To do this, it might be necessary to move the drama away from reality into a world of fable or

fantasy, but—in the fine literary tradition of allegory—it still would be possible to talk about real

issues, including Media Literacy, in allegorical terms. So, for instance, the “evil king” who the child

heroes battle against could have magic spells to change what people think or to make them act like

zombies. This would need careful thought and planning, and good writers, but if done well, it could

have great potential.

With all these ideas, it is important to remember that the aim is not to download a detailed Media

Literacy “handbook” into the minds of the audience; rather, it is to encourage a habit of critical

thinking—to prick the bubbles of received ideas and political assumptions. The point is not to tell

people what to think, but to show, in a general context, the nature of critical thinking.

Insurgent Networks

Such networks are aimed at a more sophisticated audience, so it is possible to promote Media Literacy more directly.

Satirical news review shows

The first and most obvious idea would be a satirical news show, or news review show, along the

lines of The Daily Show (until 2015 with Jon Stewart) in the US. There would be two key points: first,

the right host would have to be found—one who could appeal across the targeted region (e.g. the

whole of the Middle East) and who could carry the entire programme and be funny (a very tough

assignment); second, it would be important to poke fun at everything and not to take sides. People

would switch on to be amused, but also to take an askance view of the world—a perspective that

perhaps fits a bit better with their imperfect experience of it. The audience would probably tend to

be younger and better educated than that of a mass-market entertainment juggernaut (Jon Stewart

appealed to a pretty liberal, metropolitan demographic after all), but that would also make such

shows influential.

Current affairs comedy quiz shows

A linked idea would be to have a satirical current affairs game show along the lines of the longrunning

Have I Got News for You?, a humorous quiz show about the week’s news in the UK. Possible

segments might include: Top Ten Outrageous Propaganda Claims of the week; teams competing to

imagine the bizarre and contradictory spins different media outlets from different sides could put on

the same events; guessing which news comes from which sources or having to come up with their

own propaganda “headlines” or news lines. This would be the essence of Media Literacy but would

be fun at the same time.

Situation comedies

Another option would be a satirical situation comedy (sitcom)—for example, one set in a TV news

outlet grappling with the demands of censors and propagandists. Drop the Dead Donkey was one

such series in the UK. Scripted comedy, however, is more expensive.

New Media

Rather than bringing Media Literacy to established broadcasters or slipping it into formats, this

approach involves partnering with organisations already involved in promoting Media Literacy and

bringing production skills or funding to help them lift the quality of their content and to make it

more popular and impactful.

Several of the Media Literacy specialists mentioned in this report might make good partners. In

the Middle East, one interesting idea would be to link up with an online satirical news website like

Al-Hudood, which has become widely popular across the region while having constantly to fight

censorship and official disapproval. Help could be given to improve their video content or to lift

their professional standards so they appeal to a wider audience.

In Ukraine, an obvious partner would be StopFake.org. Rather than just having a website, we could

look to professionalise and structure their output into a “Golden Raspberry”-style countdown of the

“Top Ten Lies” and online games (“Spot the Fake!”). IREX has also been experimenting with a Media

Literacy game—again, we could take their expertise and put it together with professional producers

to make something that would “go viral” online. We should look to bring materials such as witty

graphics, funny animations, and popular comedians, as well as the tricks of music and editing that

make content more immediately arresting and entertaining; online video will be worth considering

for the simple reason that it is easier to consume and has more entertainment impact than text.

All these ideas would work online and could be distributed by social media, but this kind of material

will be ripe for crossing over into the more “insurgent” media networks considered above. For

;of propaganda could be turned into a satirical awards ceremony “event”, televised and distributed

online or via broadcasters with the nerve to take it. We should consider bringing their journalists—

and IREX’s Media Literacy trainers—into the production process for a news review show or satirical

comedy, both to make sure we keep up the standards of our Media Literacy content, and also to

bring a steady stream of new and “edgy” material for marrying up to our professional approach.

NEXT STEPS

To take forward the points in this report, I would recommend establishing a development team that

brings together people from the worlds of academic Media Literacy, policy, and media content.

Together they would work up these content ideas to the point where they could be pitched to funders,

broadcasters, and online outlets. The team should have enough capacity to grow (“crew up”, in TV

jargon) when the time comes to move from development to production, and to create pilots for the

best ideas. By working together in international teams, such a Media Literacy Entertainment Working

Group would be able to share best ideas and practices across different regions of the world.

The secret of success in the information war lies in the ability of people with something to say to

come together with people who know how to say it. There is still such a thing as the truth—or, at

the very least, something that is more true (so far as we can tell) than some other thing. Honest

journalism has held to that idea for centuries. But in a world where people can pick from such a huge

variety of information sources, we cannot rely on honest journalists being heard above the din.

So it falls to all of us to think a little bit more for ourselves—to weigh what we are being told, to debate

with a little more logic and sophistication. At times it will be tricky, but the principles themselves are

quick to grasp and the right habits easy to pick up. And in that there is a new role for the media—the

task of making Media Literacy popular.

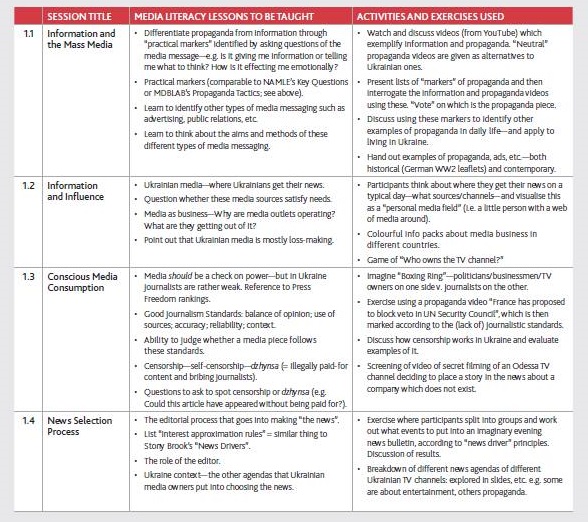

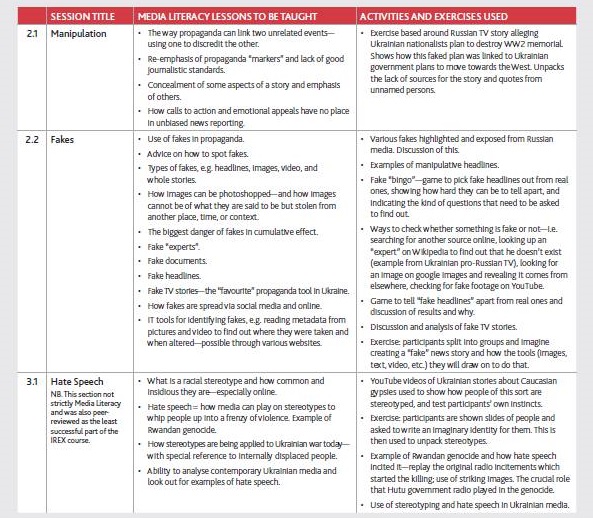

APPENDIX: IREX MEDIA LITERACY COURSE

IREX—CITIZEN MEDIA LITERACY PROJECT—COURSE BREAKDOWN

REFERENCES

1. We do not wish to disseminate the original video but parts can be seen with appropriate context and commentary in a lecture, “Frontiers of Arab Media Literacy”, by Dr Jad Melki of the Lebanese American University, around 55 minutes in. mdlab. center/2015/10/25/frontiers-of-arab-media-literacy, accessed

March 2016.

2. Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss, “The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money”, Institute of Modern Russia (New York, 2014), page 6.

3. As an example, see the Wikipedia page “Media Literacy”, subheading “Education”: “The terms ‘media literacy’ and ‘media education’ are used synonymously in most Englishspeaking nations.” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Media_literacy, accessed 9 March, 2016.

4. National Association for Media Literacy Education, “Media Literacy Defined”. namle.net/publications/media-literacy-definitions.

5. R. Hobbs, “Media Literacy and the K-12 Content Areas”, in G. Schwarz and P. Brown (eds), Media Literacy: Transforming Curriculum and Teaching, National Society for the Study of Education, Yearbook 104, Malden, MA: Blackwell (2005), pages 74–99.

6. National Curriculum in England: Citizenship Programmes of Study (applies only in England, though Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have comparable requirements). www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-englandcitizenship-programmes-of-study, accessed March 2016.

7. For example, the US National Association for Media Literacy Education’s “Core Principles of Media Literacy Education in the United States”. namle.net/publications/core-principles.

8. There are many examples but the Center for Media Literacy lists some: see www.medialiteracy.com/national-organizations.

9. UNESCO, “Communication and Information: MIL [Media and Information Literacy] Curriculum for Teachers”, page 18. www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and information/mediadevelopment/ media-literacy/mil-curriculum-for-teachers.

10. OSCE Non-Paper, “Propaganda and Freedom of the Media”, Vienna (2015), pages 2, 63 ff. www.osce.org/fom/203926?download=true.

11. NATO Stratcom, “Internet Trolling as a Tool of Hybrid Warfare: The Case of Latvia” (2016). www.stratcomcoe.org/internettrolling-hybrid-warfare-tool-case-latvia-0.

12. Institute for Strategic Dialogue, “Counter-narrative Campaigns”. www.strategicdialogue.org/counter-narrative-campaigns.

13. Stony Brook University, Center for News Literacy, “About Us”. www.centerfornewsliteracy.org/about-us.

14. Stony Brook University, Department of Political Science. www.stonybrook.edu/polsci.

15. Digital Resource Center, “Course Pack”. drc.centerfornewsliteracy.org/course-pack.

16. Digital Resource Center, Center for News Literacy, “The Phrase ‘Islamic Terrorism’ and the Power of Words”. drc. centerfornewsliteracy.org/resource/islamic-terrorism-andpower-words-0.

17. Digital Resource Center, Center for News Literacy, “Making Sense of the Campaign: Why Donald Trump is Big News”. drc. centerfornewsliteracy.org/resource/making-sense-campaignwhy-

donald-trump-big-news.

18. edX, “Making Sense of the News”. www.edx.org/course/makingsense-news-hkux-hku04x-0#.VSbFcZTF8YJ.

19. For example, see Journalism and Media Studies Centre, University of Hong Kong, “News Literacy Project in Development at JMSC”. jmsc.hku.hk/2012/09/news-literacy-project-development-jmsc.

20. Salzburg Academy on Media and Global Change, “What is the Salzburg Academy?”. www.salzburg.umd.edu/about.

21. Interview with the author, 3 March, 2016.

22. Media and Digital Literacy Academy of Beirut (MDLAB). mdlab. center/about/partners-sponsors.

23. Media and Digital Literacy Academy of Beirut, “Mission”. mdlab.center/about/mission.

24. Media and Digital Literacy Academy of Beirut, Module 1, “Syllabus: Media and Digital Literacy”. mdlab.center/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/MovehdianBassil-and-Whitehead-Generic-Syllabus-MDLAB15.pdf.

25. Media and Digital Literacy Academy of Beirut, “Advertisement Analysis”. mdlab.center/2015/09/25/advertisement-analysis.

26. Media and Digital Literacy Academy of Beirut, Module 4, “Syllabus: Media and Digital Literacy”. mdlab.center/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/MovehdianBassil-and-Whitehead-Generic-

Syllabus-MDLAB15.pdf.

27. For further definitions of framing, see Mass Communication Theory, “Framing Theory” (masscommtheory.com/theoryoverviews/framing-theory) and Wikipedia, “Framing (social

sciences)” (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Framing_(social_sciences)). For an example of Dr Melki describing how different frames can be applied to an image of a Palestinian youth throwing a stone at an Israeli tank, see his lecture “Frontiers of Arab Media Literacy”, available at mdlab.center/2015/10/25/frontiers-of-arabmedia-literacy.

28. Media and Digital Literacy Academy of Beirut, “Propaganda Tactics”. mdlab.center/2015/09/25/propaganda-tactics.

29. IREX, “About Us”. www.irex.org/about-us.

30. Interview with the author, 23 February, 2016.

31. Our own researcher attended the IREX “Peer Review Workshop” for the project.

32. Hanna Rosin, “Life Lessons”, New Yorker, 5 June, 2006. www.newyorker.com/magazine/2006/06/05/life-lessons.

33. Defined in TV terms as the following territories: Iraq, Iran, Syria, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Qatar, Oman, Israel, and the Palestinian territories (no data is available for Yemen).

34. “One Television Year in the World 2014”, Eurodata TV Worldwide (subscription access).

35. Internet World Stats, Usage and Population Statistics, “Middle East”. www.internetworldstats.com/middle.htm, accessed March 2016.

36. World Bank Open Data, “Internet Users”. data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.P2/countries?display=default.

37. Global Web Index, Saudi Arabia Market Report, IQ 2015. www.

globalwebindex.net/reports.

38. ShiaTV.net. www.shiatv.net/view_video.php?viewkey=51c9d670adcd37004f48.

39. YouTube, “The Voice Kids”. www.youtube.com/watch?v=y7KqSrXnpSg.

40. Marjan Television Network (Manoto). www.marjantvnetwork.com/News.

41. Marjan Television Network, “Shabake Nim”. www.marjantvnetwork.com/News/shabakenim/CNEWS45.

42. Marjan Television Network, “Samte No”, season 2. www.marjantvnetwork.com/News/samtenos2/CNEWS55.

43. Alhurra, “About Us”. www.alhurra.com/info/about-us/112.html.

44. Middle East Broadcasting Networks, “Fast Facts”. www.bbg.gov/wp-content/media/2013/09/MBN2pgFactSheet.pdf.

45. N. Vivarelli, “Middle East Reality Shows Boost TV Ratings, Challenge Cultural Expectations”, Variety, 25 April, 2014. variety.com/2014/tv/features/middle-east-reality-showsboost-tv-ratings-challenge-cultural-expectations-1201162352.

46. Wall Street Journal, “Streaming: Videos, On Demand in the Middle East”. blogs.wsj.com/middleeast/2014/03/19/streaming-videos-on-demand-in-the-middle-east.

47. “The Arab World Online 2014: Trends in Internet and Mobile Usage in the Arab Region”, Mohammed Bin Rashid School of Government (Dubai, 2014), page 7. www.mbrsg.ae/getattachment/ff70c2c5-0fce-405d-b23f-93c198d4ca44/The-Arab-World-Online-2014-Trends-in-Internet-and.aspx.

48. Ibid., page 9.

49. World Bank Open Data, “Internet Users” (data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.P2). As an alternative figure, the EED Feasibility Study cites research by Gemmius putting Internet

penetration at 57 percent (page 23).

50. EED Feasibility Study, page 23.

51. Population Statistics (2014), CIA World Factbook; TV Viewership, “One Television Year in the World” (2013), Eurodata TV Worldwide, page 259.

52. This according to a study commissioned by the Ukrainian NGO Telekritika, “Russian Propaganda 2014: Tendencies, Results, Influence on Ukrainian Society”. www.telekritika.ua/kontekst/2014-12-24/101919.

53. For an analysis of January 2015 by Telekritika, see Media Sapiens, “What News Items Were Withheld in January 2015”. osvita.mediasapiens.ua/monitoring/in_english/what_news_

items_were_withheld_in_january_2015.

54. Ibid.

55. As reported by G. Toal and J. O’Loughlan, “Russian and Ukrainian TV Viewers Live on Different Planets”, Washington Post, February 26, 2015. www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/

monkey-cage/wp/2015/02/26/russian-and-ukrainian-tvviewers-live-on-different-planets.

56. Television Industry Committee, “TV Panel”. tampanel.com.ua/en.

57. YouTube, accessed 2 April, 2016; EED Feasibility Study, page 42.

58. EED Feasibility Study, page 28.

59. R. Shutow, “Russian Propaganda in the Ukrainian Information

Space”, Media Sapiens, 22 January, 2015. osvita.mediasa-piens.ua/monitoring/in_english/russian_propaganda_in_ukrainian_information_eld_overview_2014.

60. EED Feasibility Study page 28.

61. “One Television Year in the World” (2013), page 258.

62. EED Feasibility Study, page 41.

63. Middle East Eye, “Jordanian Website Turns to Satire to Combat Heavy News”. www.middleeasteye.net/in-depth/features/jordanian-site-turns-sarcasm-and-satire-combat-heavynews-1364185969.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Paul Copeland is an award-winning television director, writer, and producer who has worked for UK and global broadcasters for nearly 20 years. Starting his career in the video unit of The Economist newspaper, he was moved through educational programming, current affairs, and blue-chip science and history (including the BAFTA-nominated and Banff award-winning The Great War: The People’s Story), and now works mostly in TV drama. He is also an active writer, researcher, and reviewer on historical, political, and current affairs subjects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Maria Zhdanova for her additional research.

We would also like to thank Vasily Gatov for his many inspirational ideas for the Beyond Propaganda series.

Source: REPORT | Factual Entertainment: How to Make Media Literacy Popular