Russian President Vladimir Putin has mounted a new campaign in his propaganda war with the West: The highly publicized destruction of imported food, which the government banned last year in retaliation for Western economic sanctions. This time around, though, his constituents aren’t quite with him.

The ban, aimed at the U.S. and European countries that imposed sanctions on Russia over its aggression in Ukraine, covers a long of items, including fruit, vegetables, most kinds of meat, fish and dairy products. Some have been replaced by imports from other parts of the world. In other cases, local producers have stepped up. In the first six months of 2015, Russia’s poultry output increased 11.4 percent from the same period in 2014, meat production jumped 13.2 percent, and cheese production increased 27.5 percent.

The local replacements often aren’t all that great. In a taste test of one of the bizarre cheeses that have filled Russian store shelves since the embargo, the Guardian’s Moscow correspondent Shaun Walker concluded that “the disintegrating texture is unnerving, and feels as if hundreds of tiny globules of parmesan have been left out on the pavement for a couple of weeks and then stuck back together with glue.”

To satisfy demand for the real thing, embargoed goods have been filtering into Russia. Some arrive by circuitous routes to establish acceptable provenance, or are repackaged in neighboring Belarus to pretend they originated there (I’ve seen Belorussian salmon in stores, though the landlocked country doesn’t produce it). Others are simply smuggled in: Russian customs inspectors are not known for their incorruptibility.

In a rare act of defiance, the Magnit chain of discount supermarkets, one of the country’s biggest retailers, sued the government agency charged with keeping embargoed items out of stores, claiming Putin’s decree on the food sanctions bans only their import, not their sale. A St. Petersburg court last month ruled in Magnit’s favor, a decision that would be more surprising if the company weren’t owned by Sergey Galitsky, one of Russia’s richest people.

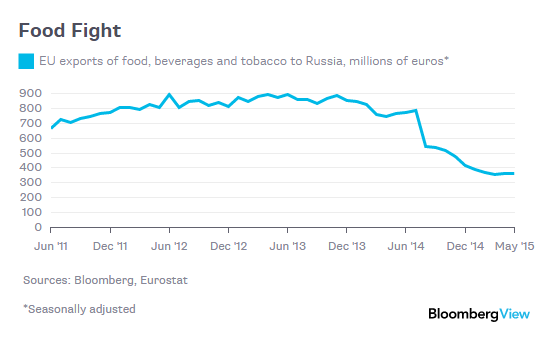

Putin, however, won’t have it. He wants his food embargo to work as effectively as before, boosting local producers and punishing Western companies that have already seen their Russian business shrink. European Union exports of food, beverages and tobacco to Russia, for example, were down more than 50 percent in May from a year earlier:

So, on July 29, Putin decreed the ruthless destruction of any banned food caught on Russian borders, starting on Aug. 6.

The decision astonished many Russians, who are no strangers to food shortages. Many still remember the long lines of the 1980s, or — worse — the starvation that accompanied the Nazi siege of Leningrad, which Putin’s own parents endured. “For every Leningrader I know food is a kind of neurosis,” journalist Valery Panyushkin, who himself comes from the city now called St. Petersburg, wrote on Snob.ru. “I’ve been carrying the memory of the great famine all my life, like a food sack on my back, a rather heavy one. And I envy Leningraders [Prime Minister Dmitri] Medvedev and Putin. By some miracle, they have freed themselves from the local neurosis.”

The Russian Orthodox Church doesn’t look kindly upon the destruction of food, either. “In essence, this is a crazy, stupid, vile idea,” Alexi Uminsky, a Moscow parish priest, wrote on the Orthodox site Pravmir.ru. “There are lots of people in our country who could benefit greatly from these goods.”

More than 280,000 people — an unusually large number for Russia — have signed a Change.org petition asking the Kremlin to repeal the food destruction decree and hand over any confiscated food to the needy. “If something can simply be eaten, why destroy it?” the petition says.

Putin’s government, however, is like a tank without a reverse gear. State television has eagerly covered the presidential decree and its implementation. The Vesti news program chose the title “Purifying Flames” for a report about the destruction of “dozens of tons” of European pork, and “Fondue, Belgorod style” for one about seven tons of cheese plowed into the ground with a tractor in the Belgorod region.

Russians have seen a lot of strange things on state TV under Putin, but never before have they been treated to a public cheese execution. The apparent goal is to spook importers. “The very information that sanctioned goods will be destroyed has played a positive role,” Yulia Melano, spokesperson for Russia’s agriculture watchdog, Rosselkhoznadzor, told Interfax news agency.

I expect the campaign will be as ineffectual as it is grotesque. Installing incinerators at customs and crushing wheels of Gouda is not going to make customs officials any less willing to turn a blind eye for the right reward. I wonder what Putin is thinking. High as his popularity ratings may be, he cannot afford to make himself look ridiculous as the economic situation deteriorates. That’s a taboo as strong as the one about throwing away food.

By Leonid Bershidsky, BloombergView