On the morning of 24 February, people in Chisinau, the capital of Moldova, were woken up by the sound of several explosions. Bombs were falling on Ukraine, most probably in Odesa, which is less than two hundred kilometres from Chisinau. In Ukraine they marked the beginning of the war. In Moldova, the blasts marked, besides a huge inflow of refugees and concerns related to trade and economy, a change in the information environment and disinformation narratives.

Several hours later, numerous young men received a text message announcing general conscription in Moldova; men aged 18 to 50 were called to enrol in the military. That was the first “grenade” on the disinformation front in Moldova. Quite quickly, the government announced that the message was false and that an investigation would be launched to identify those who spread it.

The first days in media coverage

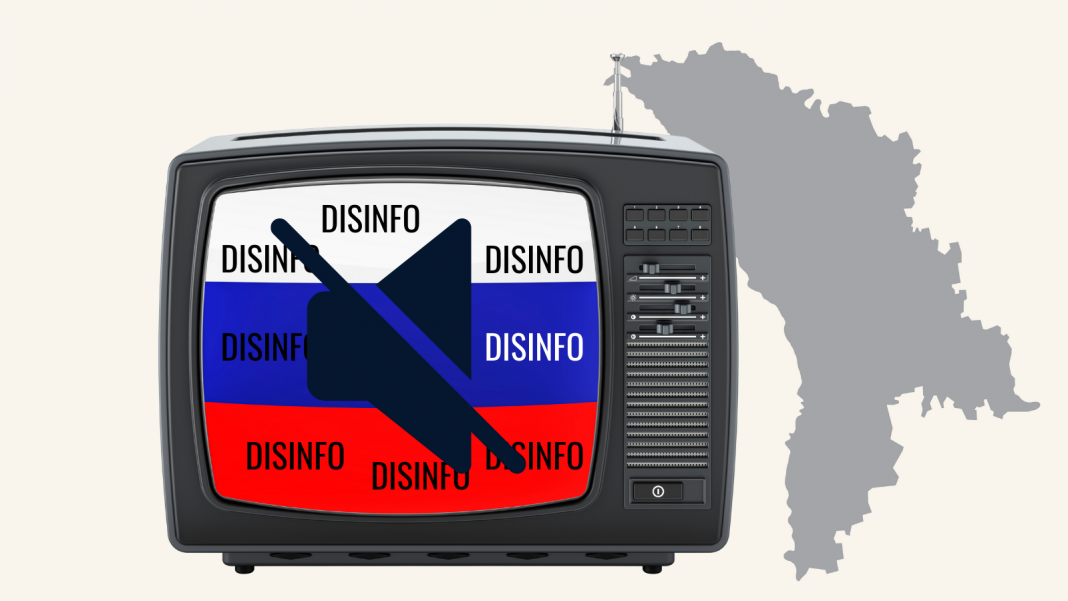

Pro-Kremlin media and Moldovan TV stations rebroadcasting Russian programming – RTR Moldova, NTV Moldova, Primul în Moldova (rebroadcasting Первый Канал), Accent TV – stopped transmitting newscasts and talk shows produced in Russia. These programmes were replaced by movies or older shows.

No official announcements were made, but experts from the Independent Journalism Centre, one of the most important local media NGOs, believe that this was done in light of the Audiovisual Council’s decision to monitor programmes of these TV stations in response to the Ukrainian crisis.

At a later stage, Socialists-owned pro-Kremlin TV stations – Primul in Moldova, Accent TV and NTV Moldova – continued to replace newscasts and talk shows from Moscow but at the same time did not inform their audience about events in Ukraine. According to an analysis by Mediacritica.md, run by the Independent Journalism Centre, these stations used “propaganda by omission, when failure to include information relevant to a particular subject may distort the recipient’s understanding of the subject in a propagandistic manner. The omission causes the viewer to create one-sided opinions, and those who resort to this technique manipulate, causing the audience to think and act in a way that is compatible with interests that are not actually their own”.

Independent media switched to highlighting what was happening in the neighbouring country, relying on international media and official Ukrainian media reports.

Russian online disinformation outlets such as KP.md and Sputnik.md did not cover the Russian invasion at all during the first hours. At a later stage, events in Ukraine were described according to the official Kremlin narrative – as a special military operation.

Online disinformation

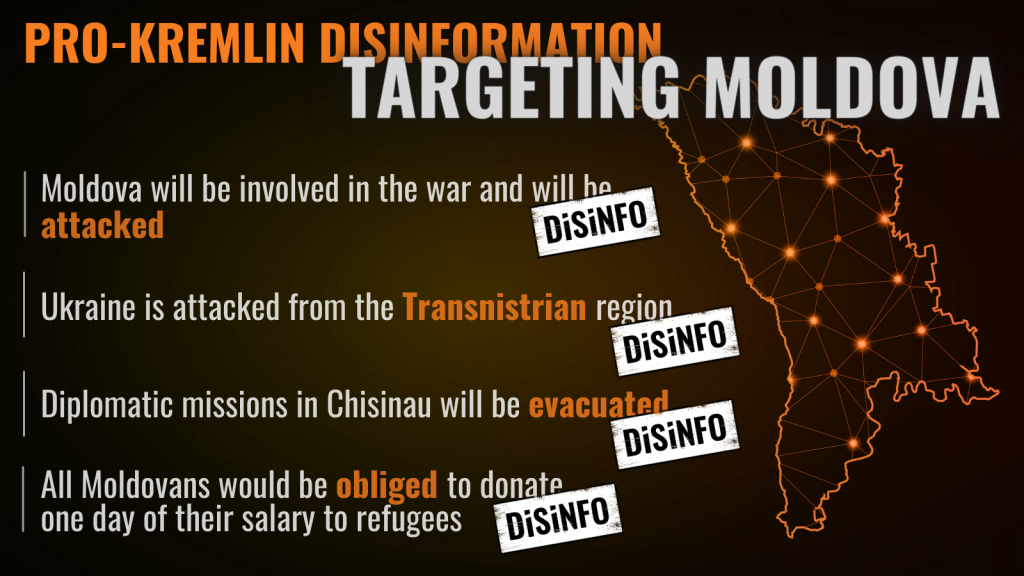

In the meantime, other disinformation messages appeared. “Moldova will be involved in the war and will be attacked”, “There is not enough foreign currency”, “American planes landed at Marculesti airport”, “Ukraine is attacked from the Transnistrian region”, “Diplomatic missions in Chisinau will be evacuated” were among the most notable narratives identified by www.stopfals.md, an anti-disinformation instrument run by the Association of Independent Press.

With pro-Kremlin TV stations still replacing Russian-produced news content and avoiding reports about the war in Ukraine, all these narratives were spread online.

Social networks, Tik Tok in particular, play the most important role in spreading disinformation. One of the first false claims about refugees assaulting Moldova’s border was made through a video on Tik Tok that gained more than 15,000 shares in several hours. Both Moldovan authorities and NGOs refuted this disinformation.

Countermeasures

The government on 24 February launched a Telegram channel called Prima sursa (First source), to expand its reach and provide official information. In two weeks, the channel gained almost 80,000 subscribers. Disinformation was debunked on the governmental website, social media channels and the Telegram channel.

Public officials, including President, Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Ministers and Ministers, appeared constantly in briefings to make announcements about relevant developments and actions taken by the authorities.

The Security and Intelligence Service blocked nine online outlets, Sputnik.md among them, for spreading hate speech and instigation to war and violence. The next day, Sputnik announced that it could be accessed from Moldova through three other addresses; the Moldovan authorities did not respond to this. In the meantime, part of the newsroom of Radio Sputnik Moldova resigned, protesting against the editorial policy of the station. “We do not want to be involved in disinformation and manipulations. We tried to maintain a social and political balance within the newsroom, but things have degraded. (…) We plead for peace and condemn any military aggression that means death”, reads the resignation letter signed by eight employees of the station. On 2 March, the Commission for Emergency Situations decided among other things to suspend broadcasting and re-broadcasting in Moldova of most programmes produced in states that have not ratified the European Convention on Cross-Border Television.

Voices supporting the Kremlin’s military aggression against Ukraine or criticising Western sanctions against Russia are relatively weak in the Moldovan information space. However, according to an opinion poll by www.watchdog.md, almost 22 per cent of respondents believe that Russia is right in this conflict versus 38 per cent who think that Ukraine is right.

Refugee crisis

After the first couple of days, the disinformation narratives moved to the refugee crisis that affected Moldova directly. Official data shows that in first two weeks of the war, almost 250,000 people from Ukraine crossed the Moldovan border. About 100,000 remained in Moldova, seeking refuge from the war. In a concerted effort and with the support of international partners, common Moldovans and the authorities responded by helping Ukrainians with shelter, goods or transport.

In recent days, a trend to denigrate refugees and discourage people from helping them can be observed. The mayor of Chisinau, former Socialist Ion Ceban, said that among Ukrainian refugees might be bad people, and Moldovans could expect thefts and robberies. Stopfals.md debunked a video shared on Tik Tok by a Moldovan influencer who filmed a selfie video talking about Ukrainian refugees who allegedly demanded alcohol, food and petrol at a fuel station in Cimislia, threatening the cashier with a gun. Newsmaker.md gathered a series of hate videos disseminated on social media, especially Tik Tok.

President Sandu said in a briefing that the authorities had noticed a campaign against Ukrainian refugees and that state institutions would investigate. She also called on people to be more careful when sharing videos on social media.

However, even after that, ex-President and former Socialist leader Igor Dodon said during a talk show that Ukrainian refugees who break Moldovan law should be sent back to Ukraine or further, to Romania.

Apparently, disinformation is going two ways. On the one hand, it portrays the situation in Ukraine with narratives such as “biological labs” having been discovered by Russians. On the other hand, it is trying to divide the local population and the refugees as much as possible. The most recent stories debunked by the authorities claimed that refugees would receive 15,000 lei (approximately 750 euro) each and that all Moldovans would be obliged to donate one day of their salary to refugees.

Fortunately, the impact of disinformation has been limited so far. Many Moldovans donate selflessly much more than one day’s salary. And almost two thirds consider, according to a survey by Magenta, that a war is going on in Ukraine and not a special military operation.