The Kremlin’s propaganda machine has been disrupting public discourse in the European Union not only through media outlets like RT and Sputnik, but also by luring European journalists, analysts, and even popular actors to support Russia’s stance. Elena Servettaz identifies several Putin apologists in the French media.

Last week, Russian Facebook was buzzing with news of the resignation of Konstantin Goldenzweig, NTV’s Berlin bureau chief, after 15 years of service. Goldenzweig told Meduza that to do his job he had “learned to strike deals with [him]self” and asked to be forgiven “for his participation in ‘the disgrace’ that is Russia’s state television.” He said that his departure had “cleared his karma.” Kostya was my classmate in Moscow State University’s Department of Journalism. He started working for NTV as a reporter while still at school; at this time, a friend of mine and I were interning for an NTV talk show called The Freedom of Speech, hosted by Savik Shuster. Years later, the two of us were fortunate enough to find jobs with independent media outlets, but Kostya stayed at NTV as it degraded into one of the Kremlin’s main propaganda instruments.While in Russia many journalists attempt to escape the Kremlin’s propaganda machine, in France, there are some journalists and politicians who rush in the opposite direction.They are ready to do anything to strike a deal with Moscow.

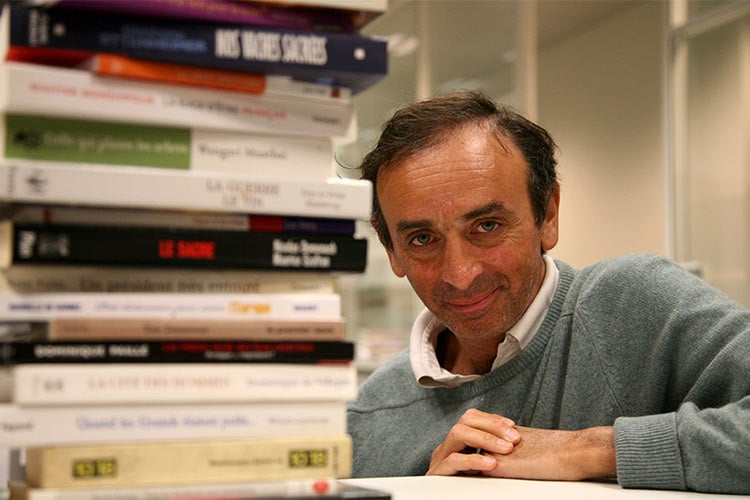

Take, for example, Eric Zemmour, former Le Figaro columnist and a regular panelist on the popular Saturday night show On n’est pas couché on France 2. Zemmour is a right-wing pundit known for his antiliberal and misogynistic claims. He has also been accused of plagiarism.

In one appearance on On n’est pas couché, Zemmour declared he wanted “no immigration, not even the regulated sort” in France. In an interview with the Italian daily Corriere Della Sera, he warned the interviewer about the risk of a civil war in France, claiming that “only Muslims” lived in French high-rise suburban neighborhoods while “French people have been forced to leave those suburbs.” Statements like these have made Zemmour a pariah, causing French politicians and even journalists to turn against him. Only Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of the far-right National Front, continued to support him, claiming that there are only three journalists in France who have “played fair” with him, with Zemmour being one of them. When On n’est pas couché presenter Laurent Ruquier finally ousted Zemmour from the show, he said he regretted the five years he had worked with Zemmour that had made the latter famous. Though Zemmour disappeared from TV screens after a succession of scandals, in 2014 he published a book titled Le Suicide Français (French Suicide), announcing the death of France. The book became a national bestseller.

This June, Zemmour found a new stage. The French-language website of the Kremlin TV channel RT (formerly Russia Today) published his op-ed entitled “Vladimir Putin Is Not a Nice Guy” (“Vladimir Poutine n’est pas gentil”), in which he analyzed the new global order in Manichean fashion. “Putin is not good, and the European Union is good, Angela Merkel is good, François Hollande is good, Barack Obama is good,” wrote Zemmour. All of them are trying “to prove that they love everyone,” he adds sarcastically, blaming the U.S. president for “having frozen the bank accounts of Putin’s inner circle” and Hollande for “refusing to supply Mistral warships that Putin had ordered from Sarkozy and that had already been paid for.” As for the past year’s events in eastern Ukraine, he describes them in the best tradition of Russian state TV: “The bad [politicians] sent their clandestine troops to support the Ukrainian insurgents. The good [ones] secretly helped to remove the Ukrainian government from power. But it is called a revolution, not a coup d’état.”

In November 2014, when RT launched its French-language service, Russian journalist and publisher Sergei Parkhomenko predicted that Zemmour would soon appear on the Kremlin’s television station: “Mark my words, [the Kremlin] will now start buying your celebs for crazy cash. And Zemmour will be the first one [for sale].”Parkhomenko added that he wouldn’t be surprised if Jean-Pierre Elkabbach and Patrick Poivre d’Arvor followed suit.

Indeed, Elkabbach, a veteran French journalist, might have a good chance of doing so after his fawning interview with Putin last June. “I will never forget this moment,” Elkabbach declared of the interview and insisted that it was “an absolutely free conversation, with no taboos and no conditions.“Elkabbach described Putin obsequiously: “I have met lots of politicians, but this first meeting with Putin, which lasted two hours, made a strong impression on me.He is charismatic and energetic, but with few niceties. He shows toughness and sometimes a coarse rigidity characteristic of shyness. Yes, I would say he is a shy man.”

While in Russia many journalists attempt to escape the Kremlin’s propaganda machine, in France, there are some journalists and politicians who rush in the opposite direction. They are ready to do anything to strike a deal with Moscow.

Jacques Sapir, a regular columnist for the French service of the pro-Kremlin news agency Sputnik International, is another enthusiast of Putin’s Russia. An economist, Sapir is always willing to bend over backwards for Putin, even if he does not admit (at least publicly) that he is the Russian president’s friend. Two years ago, one French radio station published a piece alleging that Sapir was linked to the Russian authorities. The piece sparked an immediate reaction from Sapir. He sent an indignant e-mail (which has been viewed by IMR—Ed.) to his friends and colleagues stating that the radio station had crossed a line. He also notified Alexander Nikepelov, chairman of the Kremlin-controlled oil company Rosneft (with whom he co-wrote a book on Russia’s transition from Communism, entitled La Transition Russe, Vingt Ans Après), of his displeasure and wrote a strongly worded post on his blog denouncing the allegations.

The French arm of Sputnik is open not only to Putin’s apologists in France; some French-speaking Swiss politicians are active there as well. One of them is Guy Mettan, who wrote a piece for Sputnik titled “Russophobia, a Symptom of Crisis in Journalism.” Mettan describes himself as a Swiss politician and journalist, which raises the question of how someone can be both a journalist and a politician. I posed this question directly to Mettan on Twitter. His reply was: “Yes, you can, what is the problem? … Is freedom of thought not a right for politicians as well as journalists?” I argued that one cannot combine the two positions—in democratic countries, professional ethical guidelines forbid it. Mettan’s response was that it was not for me to decide what is democratic and what is not.

Mettan holds dual Swiss and Russian citizenship, thus maintaining a strong connection with Russia. However, he has refused to comment on that issue publicly. He is also the author of Russie-Occident: Une Guerre de Mille Ans: La Russophobie de Charlemagne à la Crise Ukrainienne (Russia vs. the West: A 1,000-Year War: Russophobia from Charlemagne to the Ukrainian Crisis) (Editions des Syrtes, 2015). At the end of April Mettan appeared at the Geneva International Book Fair alongside Russia’s minister of culture Vladimir Medinsky, who had also published a book entitled The War: Myths of the USSR, 1939–1945. Interestingly, the General Consulate of the Russian Federation in Geneva tweeted about the meeting between the two “writers.”

The set of Russian propaganda channels in France includes a think tank—the European Institute for Democracy and Cooperation, headed by Natalia Narochnitskaya. The Institute’s employees appear on various French TV and radio shows to support Kremlin policy, arguing that, say, “Crimea is ours,” and organize roundtables and conferences entitled “The Great Europe of Nations: Tomorrow’s Reality?” One of these events was co-hosted by the French right-wing parliamentary member Thierry Mariani, known for his strong support of the Kremlin, and by former prime minister François Fillon, who is regularly quoted by Sputnik. The Kremlin’s party line is also advanced by Veronica Krasheninnikova, director of the Center for International Journalism and Research of Russia Today.

And, of course, we should not forget Gérard Depardieu. The famous French actor, who received Russian citizenship from Putin himself, recently declared that French people are less happy than Russians and stated that he would love to have a president like Vladimir Putin. One can legitimately wonder what the average French citizen would think if France was ruled by the same man for 15 years.

The Kremlin’s propaganda machine has, however, recently faced an unexpected obstacle. On June 18, French authorities seized several bank accounts belonging to representatives of Russia Today in France, as well as property of the news agency TASS. The decision was the result of last year’s ruling by the International Court of Arbitration in The Hague that Russian officials had manipulated the legal system to bankrupt the oil company Yukos, and that Russia will have to pay $50 billion to Yukos’ shareholders.

It remains to be seen what impact these measures will have on the propaganda channels abroad, but RT editor-in-chief Margarita Simonian has commented that RT management has already “taken precautions and measures in advance, preventing our radio and online broadcasting in Europe and other countries from being disrupted due to the seizure of our bank accounts.”

By Elena Servettaz, Institute of modern Russia