History is an important tool in the Kremlin’s propaganda and information war against Ukraine. Russian historical mythmaking is dangerous because it is the main source of legitimizing Russia’s political violence against other countries, including Ukraine. By juggling historical facts and inventing new meanings, the Kremlin justifies its territorial claims and military actions against Ukraine to the West, questions the very fact of the existence of our country, pursues division of society in Ukraine and for Russian citizens legitimizes an aggressive policy toward neighboring states.

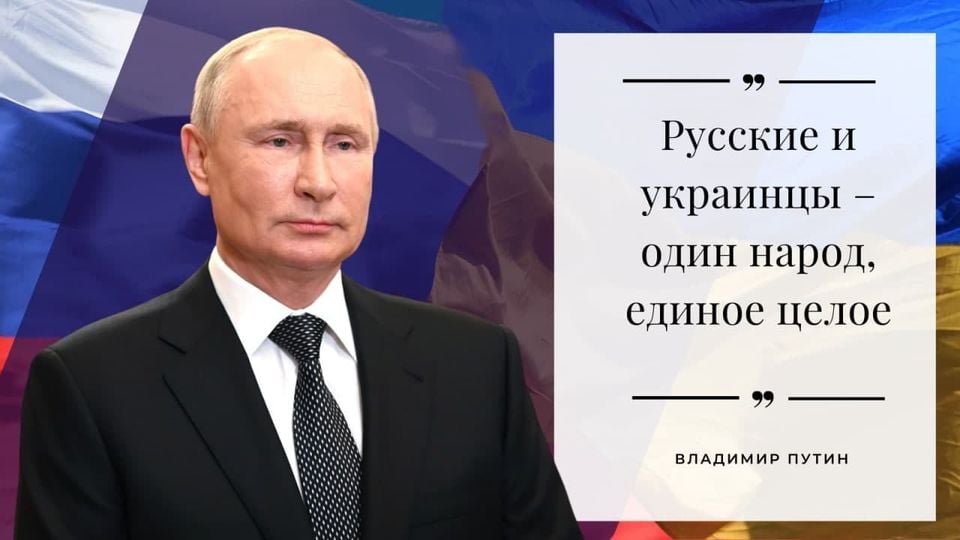

On July 12, Vladimir Putin’s article “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians” was published on the Kremlin’s website. The text appeared in two languages at once – Ukrainian and Russian. This publication was the logical continuation of a long interview with the Russian president on Russia-1 TV, during which Putin devoted a great deal of time to Ukraine. Putin’s article is of particular interest from the point of view of building a holistic Russian propaganda narrative about Ukraine.

In his article, Putin repeats both the old imperial historical myths about Ukraine (“Russia is the successor of Ancient Rus’,” the 1654 Pereyaslav Council as an act of “union” with Moscow, etc.) and those that are quite literally being formed before our very eyes: that Crimea is Russian land and the self-proclaimed separatist Donetsk and Luhansk People’s republics are historical formations with precents.

Moscow State – the only descendant of ancient Rus’

According to Putin’s version of history, after Kyivan Rus’ was brought down by the Mongol invasion in the 13th century, its statehood was transferred to the Muscovy. “History decreed that Moscow become the center of reunification continuing the tradition of Russian statehood. Moscow princes, the descendants of Alexander Nevsky threw off their external yoke and began gathering the Russian lands” Putin writes.

In his 2006 book the Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus Harvard historian Serhii Plokhy explains XV-XVI century Moscow intellectuals constructed the idea of Muscovy as the only historical successor of Rus’ because they needed to legitimize Moscow’s territorial conquests in the West. Plokhy writes: “Trying to distance the new state of Muscovy and its ruling circles from their Tatar past, the church imposed Kyiv ties on the secular elite. There was hardly a better way to break from the recent Tatar past than to emphasize the Roman, Byzantine and ultimately the Kyivan roots of the Moscow dynasty.”

The idea of the gathering of Russian lands, the conscious drive by Moscow to annex Ukrainian territories in particular, is connected to the Russian tsars’ desire to connect Kyivan Rus with Moscow.

Tsar Ivan III embraced this policy in order to legitimize his territorial claims in the west. Initially Russian diplomats stated Moscow’s claims to all of Rus cautiously and not immediately, but nevertheless did so with a persistence and consistency that could not have been possible without a premeditated concept system” writes Russian historian Pavel Milyukov. In 1493 Tsar Ivan III adopts a title that reflects this concept – the sovereign of all Rus’. Russian patrimony comes to include Kyiv (Ukraine), Smolensk (Belarus) and other citie, thereby expanding his rule and allowing himself the opportunity to expand it even further. Russian diplomats give Russian policy an expansion goal which they are able to successfully attain over the course 250 years, Milyukov notes.

In this context the concept of Moscow as the third Rome is also important. Among other things this concept justified the aggressive conquest policy of the Moscow tsars. Moscow as the third Rome posits that Moscow is the last Christian stronghold on earth and the Moscow tsars, as the successors of the Roman and Byzantine emperors, are the defenders of all Orthodox believers. Echoes of this concept are present in Putin’s article: Moscow will defend all Russians. Russians are not a national category but an ideological one, a category that can change its content depending on the Kremlin’s goals, however, the Orthodox faith and the Russian language remain the main attributes of this category.

Recommended reading:

Serhii Plokhy: The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus

1654 Pereyaslav Council as an act of “union” with Moscow

The leitmotif of Putin’s article is the idea of the commonality of the three peoples of Rus (Ukrainians, Belarusians and Russians), which is based on two pillars – a common faith and a common “homeland”. Although these ideas have their roots, as described above, in the XV-XVI centuries, this narrative was largely designed and developed by XIX century Russian imperial historians. Mikhail Pogodin argued that Russian/ Rus’ history had always weighed towards the return Russian land that had been taken away by its western neighbors. But Nikolai Ustryalov was probably the first imperial historian to fully incorporate the paradigm of “reunification” into Russian imperial history. He believed that all Slavic peoples constituted a single Russian nation, and being divided by circumstances, sought unity.

Ukrainian historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky was the first to question Russian imperial historiography’s idea of “reunification”. In his 1904 article entitled The usual scheme of Russian history and the question of rational order of Eastern Slav historyHrushevsky advocated that the idea of Rus’-Vladimir Grand Duchy-Moscow Principality-Russian empire had several significant flaws and was erroneous from its very beginnings. Hrushevsky considered the Kyivan state to be the creation of one nation – Ukrainian, and the Vladimir-Suzdal and Moscow principalities the creation of another – Great Russian. Therefore, as there was no separation, there can be no reunification.

Beginning in the 1930s USSR when Stalin’s Russian-centric model of the national question prevailed, the imperial interpretation of the Pereyaslav treaty as an act of unification of Russia and Ukraine became official history.

Analyzing the self-identity and motivations of the 1654 Pereyaslav Council participants, in his book The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, Harvard historian Serhii Plokhy tries to answer the question: was there any reunification at all?

Unable to reach an agreement about military aid with the Ottoman empire and the Crimean Khan, Ukrainian kozaks were forced to negotiate with Muscovy in order to engage them against the war with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. According to Plokhy, during the talks the Ukrainian side appealed to the tsar’s orthodox faith as a unifying factor and Ukrainian elites even recognized the Romanov’s kinship with the Kyivan Rus’ Rurik dynasty. There was however no question of any national unity or a common homeland.

Plokhy asserts that historical sources show that even Moscow did not think in terms of national community between Muscovy and Rus’. Relations with the Ukrainian kozaks were considered exclusively in terms of dynastic terminology, kozak lands were just another part of the tsar’s patrimony.

The ideological gap between Moscow and Rus’ is evidenced by the refusal of Vasily Buturlin, the tsar’s representative, to swear an oath at the kozak council. Educated in the tradition of the Commonwealth, where the king takes an oath before his subjects, Ukrainian kozaks demanded the same from the Moscow side. After Buturlin’s refusal, the kozak leadership long pondered whether to believe the Moscoe’s promises, which were not bound by an oath.

Recommended reading:

Viktor Horobets: The Ukrainian Hetman state and the Russian Dynasty before and after Pereyaslav

Ukraine as Polish-Austrian Project

In his article, Vladimir Putin mentions a project by Polish-Austrian ideologues to create an “anti-Moscow Rus’.” According to this postulate, any actions towards the establishment of a national self-consciousness and independence of Ukraine are a priori actions against Russia. In a historical context accusations of creating an “anti-Moscow Rus’” are also often addressed to Austria-Hungary, and in the modern context – to the collective West, which allegedly supports Russophobia in Ukraine.

Russian propaganda claims that the Austro-Hungarian empire invented Ukraine, encouraged military independence in order to pit Russian against Russian. Ultimately the Bolsheviks seemingly also picked up the concept that Ukrainians are different from Russians and finally implemented the idea through the creation of the Soviet Union.

After the Ukrainian language was banned in the Russian empire and nothing could be published in Ukrainian (Valuyev Circular of 1863, Ems decree of 1876) Lviv becomes the center of Ukrainian thought and learning. Manuscripts from left-bank Ukraine are brought into Lviv to be printed, various groups -dedicated to the study of Ukrainian history and folklore are formed here. Ruthenian-Ukrainian was one of the 10 official languages of the Austro-Hungarian empire. In Galicia pro-Russian movements supported by Moscow were organized to counter the Ukrainian national movement.

Russian propaganda propagates disinformation claiming that the Ukrainian blue and yellow flag is the flag of Lower Austria, thereby proving that Ukraine is an “Austrian project”. In fact, the Ukrainian flag stems from the Galician heraldic colors and the Rus Galician kingdom of XIV-XV centuries.

Recommended reading

Yaroslav Hrytsak: Sketch of Ukrainian History. The Formation of a Modern Nation XIX-XX centuries.

Crimea – Russian land

Vladimir Putin mentions Crimea several times in this his latest opus, how it became part of the Russian Empire, what peoples live on the peninsula, how their cultural and religious rights were respected in the empire, how Crimea was allegedly handed over to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic “with gross violations”, how Crimeans rejected the “anti-Russia project, made their historic choice” and returned to Russia.

The myth of Crimea in Putin think includes several distinct smaller myths: for Russian soldiers Crimea is a place of valor and glory and a cradle of Russian spirituality; Sevastopol is a Russian hero city and the homeland of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. The full message of the Crimea is ancestral Russian land vein was most completely conveyed during Vladimir Putin’s speck to the State Duma and Federation Council deputies in March 2014 after Moscow annexed the Ukrainian peninsula.

“To understand why this choice was made, it is enough to know what Russia has meant and means for Crimea and what Crimea means to Russia. Literally everything in Crimea is permeated by our common history and pride. All these years, citizens and many public figures have repeatedly raised this issue, saying that Crimea is ancestral Russian land and Sevastopol is a Russin city” Putin said.

Contrary to Putin’s claims, the earliest Slav settlements appeared in Crimea no earlier than the 13th century and constituted an insignificant minority well into the 1860s. After the failures of the Crimean War the Russian Empire changed its national policy towards Crimea’s inhabitants. Moscow launched a repressive campaign against the Crimean Tatars, often forcing them to emigrate to the Ottoman empire. Only in the beginning of the 20th century did Russians begin to outnumber Crimean Tatars on the peninsula. The national makeup of Crimea changed only as a result of repressive Soviet policies, particularly the massive deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944.

Kremlin propaganda promotes a “sacred” version of “Russia’s historical right to Crimea” for its own population, but for the West, it opts for a legal version. “In 1954, the Crimean region of the RSFSR was transferred to the Ukrainian SSR, in gross violation of the legal norms in force at the time,” Putin writes in his article.

The process of handing Crimea over to the Ukrainian SSR took more than six months and passed through all required and appropriate legislative phases of that time. Russia’s modern establishment questions the legitimacy of the February 19, 1954 Supreme Soviet Decree transferring Crimea to Ukraine. The transfer was indeed approved unanimously by a Supreme Soviet Presidium meeting, but the Presidium did not have the authority for such a move. This was the prerogative of the Soviet parliament. That is why on April 26, 1954 the Supreme Soviet of the USSR enacted the law “On the Transfer of the Crimean Region from the Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic to the Ukrainian SSR” and passed another law approving the Soviet Presidium decree. These laws enshrined amendments to the Soviet Constitution, Crimea is deleted from the list of administrative-territorial units of the Russian Federation and included in the list of Ukraine’s administrative-territorial units.

During the December 1, 1991 referendum on Ukrainian independence, 54.2% of the Crimean population voted in support of independence.

Recommended reading:

Serhiy Hromenko. 250 years of falsehoods: Russian myths about the history of Crimea

Self-proclaimed people’s republics as historical creations

According to Putin, the residents of Donetsk and Luhansk, just like the Crimeans, unable to come to terms with Kyiv’s anti-Russia policies, took advantage of the right to rise up and were forced to take up arms. Millions of Ukrainians rejected Kyiv’s anti-Russia policies, claims the Kremlin leader. The Crimeans made their historic choice. The people in eastern Ukraine tried to defend their position peacefully. But they, together with their children, were labeled as separatists and terrorists and threatened with ethnic cleansing and force, Putin claims. And that is why Donetsk and Luhansk residents took up arms, to protect their homes, their language, their lives. After the pogroms that rolled through Ukrainian cities, after May 2, 2014, the horror and tragedy that took place in Odesa, where Ukrainian neo-Nazis burned people alive, did they have a choice, Putin asks disingenuously. Bandera followers are ready to unleash similar massacres in Crimea, Sevastopol, Donetsk and Luhansk. They won’t abandon such plans even now – Putin writes.

Justifying Russia’s 2014 moves Putin not only resorts to the right to rise, but he also harks back to earlier “state formations” in Donbas, reminds us that on the eve of Communism there existed a Donetsk Kryvyi Rih Soviet Republic. Because of inconsistent Bolshevik policies and their social experiment did not become part of Soviet Russia, but could have. Lenin categorically refused that such a formation become part of Russia and insisted on the creation of one government for all of Ukraine, and because of Lenin’s inconsistent policies the Donetsk basis mistakenly ended up becoming a part of Ukraine, according to Putin’s version of history.

Lenin in fact believed that it was necessary to support national movements throughout the entire territory of the former Russian empire. He believed that the borders of the newly created Soviet constituent republics should be based on a national basis and not an economic one. At that time, Ukrainians were living on the vast majority of Donbas territory. However, in 1925 the Shakhtynsk region, which had a majority Russian population and the Tahanrih region, which had a majority Ukrainian population, were both absorbed into Soviet Russia. The border established in 1925 between Ukraine and Russia is the current existing border between the two countries.

The history of the Donetsk Kryvyi Rih Republic is actively held up as an example in the separatist Donetsk and Luhansk enclaves whose leaders often refer to this formation as their predecessor state.

Historian Stanislav Fedorchuk calls the Donetsk Kryvyi Rih Republic a Bolshevik puppet state that lasted an entire month. When Ukraine’s Central Council declared independence in January 1918, a group of Bolsheviks based in Kharkiv decided to seize power and declare a Bolshevik republic on Ukrainian territory. This was the initiative of a handful of Bolsheviks, among them the terrorist Artem Serheyev, who was one of the godfathers of this failed project, Fedorchuk explains.

It was of paramount importance not to hand the Donbas over to anyone. That is why this Donetsk Kryvyi Rih republic was concocted, whose “government” languished for months in the city of Bakhmut. Then the German advance began and this government hopped on a train and left. That was the republic” says Donbas history specialist Serhiy Tatrynov.

Tatarynov points out tha the Donetsk Kryvyi Rih republic was just one of many similar spontaneous soviet republics whose goal was to grab territory before another political force could.