‘Have you seen the news from Paris? Just awful isn’t it’. This WhatsApp message was the start of a long evening cross-referencing updates on Tweetdeck, trying to understand what was happening on the ground in Paris and realising the phrase ‘just awful’ couldn’t do justice to the horror unravelling, Claire Wardle wrote for The First Draft.

Unsurprisingly, as always happens in chaotic breaking news situations, the rumours emerged quickly and were shared widely.

In the first couple of hours there was the claim that the lights on the Eiffel Tower were turned off as a mark of respect, when actually they are turned off every night at 1am; the video of a fire in a refugee camp in Calais that turned out to be from earlier this month; and a tweet from Donald Trump about gun control that he actually sent after the Charlie Hebdo attacks from January. And perhaps worst of all, the sharing of a photo from an Eagles of Death Metal concert from the previous night in Dublin, with people saying it was from inside the Bataclan concert hall.

Craig Silverman has written extensively about the spread of misinformation, and he has argued that news organisations should play a more active role in debunking false information.

Twitter has been described as a self-cleaning oven, and while these rumours from Paris were ultimately debunked, it took longer than it should have done, and it took even longer to break out of the ‘news nerd’ bubble to reach wider audiences.

Certainly, around these events, there have been more efforts by news organisations to debunk information than I’ve seen previously. In the 24 hours after the Paris attacks, I counted at least five articles with titles along the lines of ‘The online rumours about Paris you shouldn’t believe’. There have been examples in BuzzFeed, BBC, Quartz, The Atlantic and France 24.

While I don’t want to be churlish, this isn’t good enough. These reflective round-up pieces published after the fact are too late.

This example from Mashable shows that it is possible to do live updates. By ‘responding’ to their original tweet, it was possible to keep a correction connected to an original tweet. But as is often the case, the correction gets far fewer RTs than the original false piece of information. (As of 12:40 ET on Monday, 16 November, the original, incorrect tweet has 2,816 retweets while the correction has just 550.)

In fact, the Eiffel Tower rumour got particularly out of hand when the parody account @ProfJeffJarvis tweeted the line “Wow. Lights off on the Eiffel Tower for the first time since 1889” (to make fun of all of the false tweets about the French landmark). That tweet itself then went on to get around 30,000 retweets, including at least one news organisation re-tweeting it as fact.

We need a live ‘service’ where debunking happens in real-time on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Chris Blow, a designer at Meedan (a member of the First Draft Coalition), wrote a wonderful piece last week about designing for debunking. He referenced the work done around Hurricane Sandy by Alexis Madrigal, Megan Garber, Chris Heller and Tom Phillips. You probably know those posts, photos of sharks swimming in shallow water with a big red circle with FAKE slapped in the middle.

Where was this service for the Paris attacks? It’s three years since Hurricane Sandy, but we’re no nearer to sorting this out.

Who should do it? A social media news agency like Storyful? A social news service like Reportedly? A public service broadcaster like the BBC? Or leave it to the platforms? Should the Twitter Moments team step up during stories like this?

Three years ago, when Hurricane Sandy highlighted how quickly rumours could spread, the social networks were simply platforms. Having them play an active editorial role seemed inconceivable. But as they all move into the publishing space more aggressively (Twitter Moments, Snapchat Live, Apple News, Facebook Instant Articles), it doesn’t seem so strange to consider that they might need to add debunking to their list of responsibilities.

When I was training BBC journalists in UGC and verification between 2009–2011, the role of the BBC in debunking social media content was raised frequently. It was always countered with the argument that if you debunk some stories, you need to debunk them all, because by not debunking a story, you’re effectively suggesting it’s true.

Staying across all social content, verifying publicly in real time, involves significant resourcing challenges but on a story as important as the Paris attacks, when there are so many people following along on social media, there is a clear need. Round-up articles the following day are not good enough. We need a service for live debunking in real time.

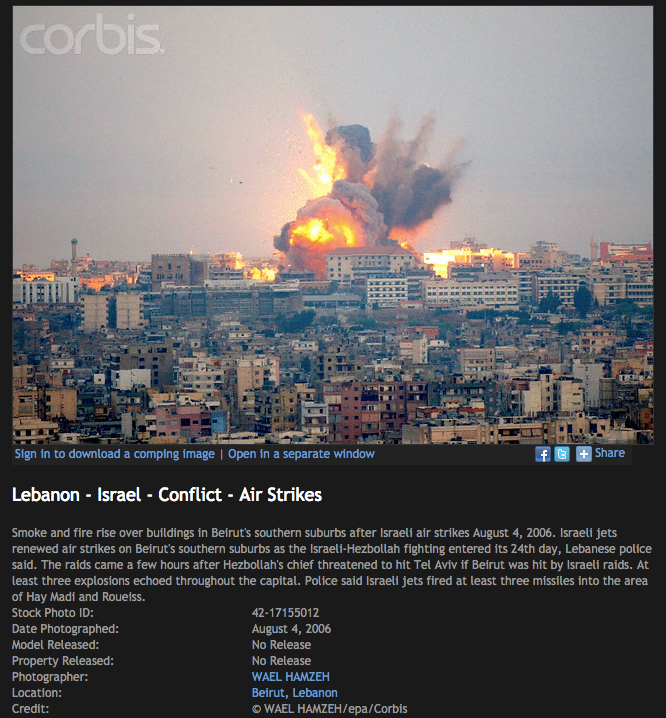

Yesterday, Jack Jones, a British YouTube prankster, with almost 86,000 followers on Twitter, posted this image.

This image is from August 2006 and a simply reverse image search means you can find the original very quickly and easily.

Jack Jones’ post, despite being told that the photo was not from the Beirut bomb on Thursday 12th November, is still up on Twitter. As I type, it has over 50,000 RTs and 36,000 likes.

Journalists can retweet this tweet and add their own typed text of FAKE, but it means the original tweet stays out there, with no-one to challenge it. It will be re-found in the coming days and more people will share it.

While many at the platform level believe in the self-cleaning oven analogy, I don’t think it’s working. Whether it’s photoshopped images of refugees, or old images of looting re-shared during the Baltimore protests, or the images connected with the Paris attacks, we’re not talking about funny shark photos here. We’re talking about something much more serious.

Fake information in these situations has the potential to impact the way people think about other people, people of other races, people of other religions. This is more than simply ensuring journalists verify content before publication. This is about doing what we can to ensure potentially damaging false information is stopped as quickly as possible.

We need to develop a way to develop a simple visual language for debunking false information and we need to talk about who will ensure this ‘language’ is added to the social content circulating on platforms. Whether it’s an accepted ‘debunked’ emoji, a Snapchat-type layer or sticker, or initiatives driven by the social networks themselves, there needs to be a universal icon. The networks share the the blue verification tick and the hashtag. We need a new shared icon.

Asking everyone to run a reverse image search before they re-share an image on social media is not working. It’s time we look again at possible solutions.

Update: Stacy-Marie Ishmael, Managing Editor for Mobile News at BuzzFeed News has just contacted me on Twitter to point me to the realtime debunking work that carried out by BuzzFeed journalist Adrien Sénécat, and the account Vérifié, linked to the French BuzzFeed account. It really is very impressive, and the use of the big red ‘FAUX’ lettering is exactly what I discuss here.

I wish I had seen these on Friday night. I didn’t.

How do we ensure that this type of journalism is the norm during a breaking news event?

By Claire Wardle, First Draft

Claire Wardle is a co-founder of Eyewitness Media Hub, a First Draft coalition member, and research director at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism

For First Draft on Twitter for more stories and case studies on social newsgathering, verification and debunks