By Halya Coynash, for Human Rights in Ukraine

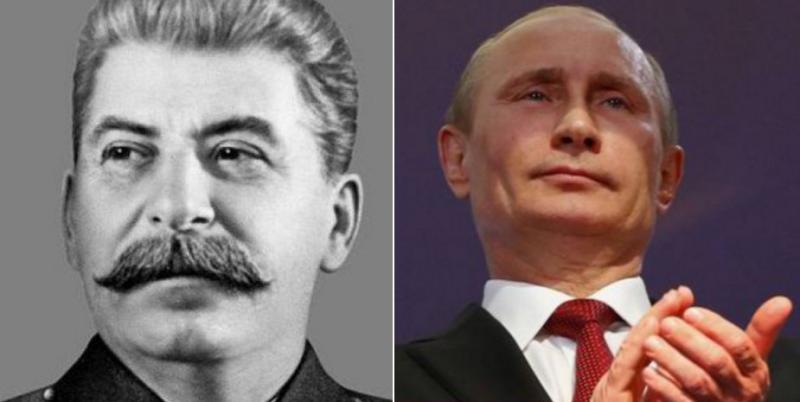

Nothing should surprise us when Russian President Vladimir Putin goes on record warning against ‘excessively demonizing’ a dictator responsible for the death of millions, and that same dictator, Joseph Stalin, is considered ‘the most outstanding figure of all ages and nations’ by a terrifying 38% of Russians polled. Yet the news that the Moscow Law Academy has erected a monument to this mass murderer is still profoundly shocking. So too is the fact that only one voice has thus far been heard in protest.

Henry Reznik is a prominent Moscow lawyer, who recently represented Vladimir Luzgin, the Russian prosecuted for reposting a text which states quite correctly that the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany both invaded Poland in September 1939. He was, until now, a professor at the Moscow Law Academy, but is unwilling to work for an institution which joins in the general whitewashing of Stalin underway in Putin’s Russia.

Reznik’s brief explanation on Ekho Moskvy is entitled “We’re not demonizing, we’re whitewashing [Stalin]”.

He writes that he only learned on Sunday that a marble memorial plaque to the dictator has been hung on the wall in the main auditorium. The words read only that Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin spoke here in June 1924 after the XIII Congress of the Russian Communist Party.

If that sounds innocuous, try imagining such a memorial plaque to Adolf Hitler. For the relatives of the victims of the Soviet Terror, the GULAG, Holodomor, the Deportation of Crimean Tatars, and countless other crimes, there is no difference.

Reznik says that he initially thought this must be fake news, but has now understood that it is not, and says that he is resigning and will never set foot in this desecrated building.

How could such a monument appear in a law institute, he asks?

“The first thing that the Bolshevik leader did was to bury the law. Stalin means mass extra-judicial bodies and repression; special sittings of three individuals or two; legalized torture; the elimination of independent courts, of the presumption of innocence and of adversarial legal process; the deportation of entire peoples.

We are still unable to overcome the traditions of Stalin’s ‘socialist legality’. Stalin is anti-law. And in honour of the grave-digger of LAW, the main value of contemporary civilization, a memorial plaque has been hung in the temple of legal science. No, that’s it, this is the limit and I am resigning from my post as professor”.

In a post-scriptum, Reznik recalls Putin’s words about not ‘excessively demonizing’ Stalin, spoken in his interview to American filmmaker Oliver Stone. It is not demonization that should be a problem for the regime, he points out, but rather the whitewashing of the dictator. There are plenty of his descendants in Russia today, those who bow to the dictator and hate freedom and democracy. They’re not in hiding now, and can be found even among law specialists.

Under Putin, there is no need to conceal admiration for Stalin, quite the contrary. In an address to history teachers in June 2007, former KGB officer Putin expressed concern about the presentation of Russian history. A manual for teachers appeared shortly afterwards, in which the author, Alexander Filippov described Stalin as “one of the most successful leaders of the USSR”. Stalin’s aim in both domestic and foreign policy, it was stated, had been the restoration of the Russian Empire. The purges had “led to the formation of a new governing class, able to cope with the task of modernization given the shortage of resources – unwaveringly loyal to the upper echelons of power and irreproachable from the point of view of executive discipline”. It was material like this that by October that year made Putin welcome “certain positive moves”, noting that “up till quite recently we read things in textbooks that made our hair stand on end…”

The Perm-36 Museum on the site of the worst Soviet political prisoner camp was forced to close, and has since been turned into a grotesque parody, focusing more on positive information about the guards and prison administration, than about the political prisoners. There have been ongoing attempts to silence the Memorial Society, and one of its most prominent figures Yury Dmitriev has been in prison for the last six months on manifestly wrongful charges.

In the meantime, monuments to Stalin have begun appearing, as well as highly doctored information about the dictator’s role in the Second World War.

Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky has spoken positively of the place the dictator holds in the country’s memory and Olga Vasilyeva, Putin’s recent choice for Education Minister, is known for an extremely specific view on Stalin and for remarks denying the number of his victims. The reappearance of portraits and busts of Stalin reached a crescendo in 2015 around events marking the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II

Ten years of such ‘positive moves’

In January 2017, the Levada Centre found a record number of Russian citizens (46%) viewed Stalin “with admiration, respect, or liking” (4%, 32% and 10%, respectively). In June, the same centre reported that the number of people critical of Stalin’s role in the Second World War had reached a record low.

This week, the Levada Centre revealed the latest results of a survey repeated every five years since 1989, in which Russians are asked to name the most outstanding figures ever. According to the table, the list is open, with respondents themselves naming people. If in 1989, only 12% named Stalin, that figure now stands at 38%, with Putin and the great poet Alexandr Pushkin tied in second place with 34%. Although it was the thought of most Russians naming Stalin as most ‘outstanding’ that was widely reported, the percentage of those naming him had actually fallen from 42% since 2012, while Putin’s rating had risen 12%. There are almost no famous world figures in the list, with Napoleon Bonaparte named by 9% of the respondents, and Albert Einstein and Isaac Newton each getting 7%.

Putin claimed to Oliver Stone that the so-called ‘demonization’ of Stalin was aimed at undermining the Soviet Union and Russia. With the country’s population becoming poorer and poorer, it is a bitter irony that a former KGB officer is using a murderous monster who killed millions of Russians, Ukrainians and others to inculcate rejection of democracy and a false sense of unity against ‘hostile’ countries, alien values – like democracy and freedom.

By Halya Coynash, for Human Rights in Ukraine