At MisinfoCon, stopping “fake news” wasn’t the only focus: Issues from news literacy to newsroom standards and reader empathy to ad revenue were all up for discussion.

By

The spread of misinformation, as well as deliberate, fabricated news content online, has many heads, and no single weapon exists to defend against it.

At MisinfoCon, a summit this past weekend hosted by the First Draft Coalition, the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard, and Hacks/Hackers, the focus was on an immediate and executable range of actions: checklists, educational campaigns, tech solutions, community engagement projects, diversity efforts, and improving business models. After all, “fake news” has evolved to mean many things (apparently, including “stories one personally dislikes“).

Now you can stop using “fake news” NAILED IT #misinfocon pic.twitter.com/7FtUKRs1Sj

— Shan Wang ☃ (@shansquared) 25 февраля 2017 г.

The convening of more than a hundred journalists, developers, technologists, librarians, and educators (plus Jestin Coler, of Denver Guardian fame/infamy, who was a very good sport and also very insightful) was equal parts hackathon and DIY seminars and freeform side conversations. (You can watch videos of the lightning talks that were presented at the Nieman Foundation on Friday here, before the open discussions and studio part of MisinfoCon kicked off over the weekend.)

So many ideas! #misinfocon pic.twitter.com/gSkxE0ct3z

— MisinfoCon (@misinfocon) 25 февраля 2017 г.

Here are some of the ideas to come out of the weekend that address the various facets of the misinformation (and disinformation) problem, from the reader side to the newsroom side to the platform side. Note: This was not a competition and this list is not ranked! All presentations are available here. All notes from Saturday morning discussions on everything from how to provide better tools for readers to vet news sources to understanding the cognitive science concepts underlying social sharing are available here, and you should absolutely check them out.

Visualizing news inequality

The Pope didn’t endorse Donald Trump for the presidency; that’s an easy story to debunk and mark as fake. The Seattle Tribune marks itself as satire; it’s not a real news source serving the city. But maybe readers are also inclined to believe patently false stories that appear on their feeds, in part because there are no legitimate news sources that serve their geographical area, or serve it in any meaningful way.

One team suggested publicizable coverage maps of how news organizations are allocating their attentions, opening up newsrooms to more public critique, and also nudging them to be more critical of what they’re choosing to cover. The team presented two graphs based on data from the geotags on around 1,500 stories from Maine’s Portland Press Herald, and it’s clear from the rough analysis that Trump voters live disproportionately in areas of Maine that get less coverage from the newsroom:

The team is calling for news organizations to replicate these types of analyses and building open source tools to make this kind of work easier to do.

Fake news sites and the programmatic advertisers who love them

Google and Facebook have said they’re trying to stem the ad-network revenue fake news sites generate, but scams are still happening. In addition, there are grassroots efforts target individual sites, most notably Breitbart, specifically for their content, shaming advertisers via Twitter to blacklist the site.

One team suggested spending some more time crafting a real list of sites deliberately posing as news sites, and building a tool to offer (or sell) to advertisers to more comprehensively block fake news sites:

1. Build a system for rating sites

2. Create a list of certified fake news sites

3. Sell/provide the list to advertisers or tech partners

4. Encourage advertisers to apply this as a filter

5. Eliminate the largest contributors to the main source of funding for fake news

An empathy “accelerator”

The Christian Science Monitor is betting big on constructive, non-depressing (but paid-for) newsCan Marketplace reach an audience beyond those who already care about explainer journalism?Ezra Klein hopes Vox can change the fact that “people who are more into the news read the news more”

The Christian Science Monitor is betting big on constructive, non-depressing (but paid-for) newsCan Marketplace reach an audience beyond those who already care about explainer journalism?Ezra Klein hopes Vox can change the fact that “people who are more into the news read the news more”Post-election, many newsrooms have embarked on reinvention projects (we checked in on several) to angle for readers they may have passed over until now and to puncture even a tiny hole in the filter bubbles of their regular readers. News organizations are also connecting voters on different ends of the political spectrum, sometimes in person.

Is there some way to standardize some of that work? One team offered news outlets a formalized audience engagement framework — an “empathy accelerator” — to help newsrooms facilitate discussions with people from groups who may not have otherwise ever interacted with each other.

Standardizing standards

News organizations are facing a problem of messaging and are disconnected from their readers. One team — whose initiative was dubbed “Changing the Narrative” — will be releasing today a full list of must-dos and strategies for newsrooms on higher-level issues, such as:

— Story generation after a new political development (covering audience needs, not media ego)

— Techniques for humanizing journalists

— Demystifying the process of journalism

— Figuring out what audiences want/need versus reporting based on perceived needs

Another team offered some suggestions for improving the efficiency of fact-checking — both the checks themselves and their dissemination — worldwide, through a new data standard to:

— Synchronize data among fact-checkers, journalists, and platforms

— Reduce time-to-market of facts by reducing repetitive work.

— Increase reach by orchestrating publishing from different outlets to different audiences

— Help build smarter news tools browser extensions, “preemptive fact checking”

Educational programming

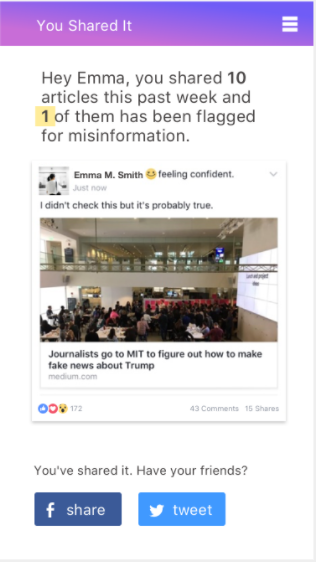

Several projects focused on improving reader awareness of the news they see on their social feeds, as well as what they’re choosing to share. The Fake News Fitness team offered a browser extension that, like the News Literacy Project’s Checkology program, walks users through an assessment of a link they enter into the tool. Another team suggested an interactive experience (app? web quiz? e-course?) that teaches readers about the various forms misinformation can take, and shows them examples of their own problematic shares.

On the reader-education side of things, one team, 22 Million By 2020, is going broadest of all: It’s trying to find partners for a nationwide news literacy and civics campaign leading up to the 2020 election (22 million refers to the number of teenagers in the U.S. who will hit voting age by then), and will convene again in September of this year to hammer our the details, including spreading a curriculum to schools.

By